|

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 832, August 2, 2015 The war on gold

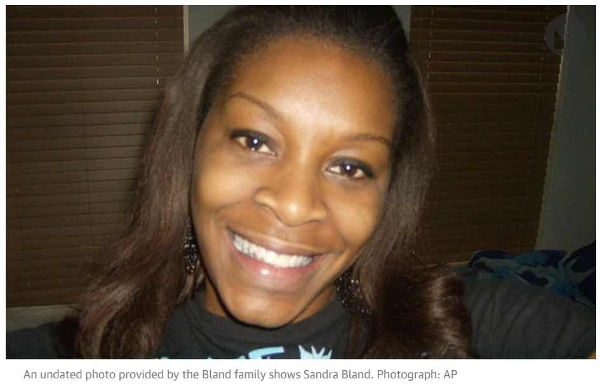

No, Ordering Sandra Bland Out Of Her Car Was Not a Lawful Police Order

Attribute to L. Neil Smith's The Libertarian Enterprise

You have probably heard the constant refrain from commentators, lawyers, and legal scholars that ordering Sandra Bland out of her vehicle that day in Prairie View, Texas may have been bad policing but it was legal. For example, CNN legal analyst Danny Cevallos wrote, "If your motor vehicle is lawfully stopped for a traffic violation, police can order you out of the car. Period." This Texas attorney begs to differ. Any freedom-loving person watching the dash cam video of the stop and arrest of Sandra Bland should be disturbed by the conduct of Trooper Brian Encinia. When he stopped Ms. Bland for failure to change lanes without signaling, all he needed to do was simply run his routine license, registration, insurance, and warrant checks, issue to Ms. Bland her citation or warning, and let her go. Instead, Encinia demanded that Ms. Bland treat him like God Almighty. He inquired about her whereabouts and her mood and even demanded that she put out her cigarette. When she questioned the wisdom and legality of his request, he angrily demanded that she exit her vehicle. My question to this CNN legal analyst who apparently believes that police power is absolute would be this: Is a police officer legally permitted to order a female driver out of her vehicle because he wants to see how she looks standing up in her skirt? If such an order under my hypothetical is an abuse of power, then is not Brian Encinia`s order to Sandra Bland to exit her vehicle for simply questioning the need to put out her own cigarette in her own car also an abuse of power? As this article shall demonstrate, a police officer generally does have the authority to command a motorist to exit a vehicle during the routine traffic stop, but a police officer must end his or her traffic stop when the objective of the stop is fulfilled. Moreover, the authority given to police officers to order motorists out of their vehicles was given to protect the safety of the officers and of others. Therefore, the command of Texas State Trooper Brian Encinia for Sandra Bland to step out of her vehicle after the purpose of his traffic stop was fulfilled and as mere retaliation for her questioning the need to extinguish her cigarette was not only inappropriate, but also illegal. Illegal under both United States law and Texas law. The facts of the case are as follows: Texas State Trooper Brian Encinia was driving through an intersection in Prairie View, Texas on the afternoon of July 10, 2015 near the campus of Prairie View A&M University. The trooper abruptly approached a vehicle in front of him, that driven by Sandra Bland. Ms. Bland changed lanes to get out of the trooper's way, and within seconds, Trooper Encinia activated his flashing overhead lights, pulled behind her, and conducted a traffic stop. Trooper Encinia walked up to the passenger-side window, cited the reason for the stop, and asked Ms. Bland where she was going, what she was doing and for her driver`s license and insurance. After answering the trooper's questions, Ms. Bland delivered her license to him. The officer said, "Give me a few minutes, alright?" and walked back to his car to issue a warning. About five minutes later, Trooper Encinia walked up to Ms. Bland's car, this time on the driver`s side. He handed Ms. Bland a warning. As Ms. Bland was apparently signing the warning, Trooper Encinia asked Ms. Bland why she seemed irritated. Ms. Bland proceeds to explain that she switched lanes because she saw him accelerating behind her and wanted to let him pass. "So, yeah, I am a little irritated," she said. "But that doesn`t stop you from giving me a ticket." Trooper Encinia then asked Ms. Bland to extinguish her cigarette. Ms. Bland responded, "I`m in my car, why do I have to put out my cigarette." Trooper Encinia then ordered Ms. Bland to exit her vehicle, saying, "Well, you can step on out now." Ms. Bland then argued that she should not be ordered to exit her vehicle because of a mere failure to signal. The officer then forced himself into the vehicle and threatened to shoot Ms. Bland with an electroshock weapon called a Taser gun. Under much protest, Ms. Bland finally exited the vehicle after which the trooper placed her under arrest. Three days later, Ms. Bland was found dead in her jail cell, reportedly from a suicide. Law enforcement apologists and defenders of the trooper`s actions are quick to argue that it was within Trooper Encinia's right to order Ms. Bland out of her vehicle. Even critics of the trooper and defenders of Ms. Bland have conceded this point. They all cite a 1977 U.S. Supreme Court case of Pennsylvania v. Mimms in which the court held that a police officer, during a routine traffic stop, does not violate the Fourth Amendment by ordering a motorist to exit his or her vehicle. An examination of this case as well as others, however, shows that the right of a police officer to order motorists out of their vehicles is not absolute. As a matter of fact, there are hardly any absolutes when it comes to constitutional law. The Mimms case involved the stop of Harry Mimms by two Philadelphia police officers for driving an automobile with an expired license plate. Although the officers stopped the vehicle merely to issue a traffic summons, one of the officers approached and asked respondent to step out of the car and produce his owner's card and operator's license. In the Mimms case, it was the practice of this particular office to order all drivers out of their vehicles as a matter of course whenever they had been stopped for a traffic violation. This practice had been adopted as a precautionary measure to afford a degree of protection to the officer. The U.S. Supreme court upheld this practice on those grounds. A 38-year-old Supreme Court case upholding the ordering of motorists out of their vehicle during routine traffic stops for purposes of safety should, therefore, not be construed as giving police officers the legal authority to order the exit of all motorists for any and every reason. Please also notice that the facts of the instant case can be clearly distinguished from the Mimms case. In Mimms, the reason (or at least the pretext) for ordering the motorist to exit the vehicle was safety. In the case of Sandra Bland, the reason the Texas State trooper ordered her out of her vehicle had nothing to do with safety. It was all about the officer's ego. The order to exit the vehicle came after Ms. Bland questioned the need to remove her cigarette. It had more to do with frustration with an "irritated" motorist than with any concerns for the safety of Trooper Encinia. Another factor that negates the legality of the order of Trooper Encinia for Ms. Bland to exit her vehicle is the timing of the trooper's order. The command for Ms. Bland to exit the vehicle did not come before or during the issuance of the citation, but after. Trooper Encinia had already written the traffic warning and delivered it to Ms. Bland. The only thing remaining to be done was for Ms. Bland to sign the warning, which she was in the process of doing. After Ms. Bland signed the warning, the stop should have concluded. Instead, the trooper inquired as to why Ms. Bland was upset, asked her to extinguish her cigarette, and ordered her to exit the vehicle when she challenged his request. The trooper's actions violated the legal principle that a traffic stop ends when the objective of the stop is complete rather than whenever the officer feels it is. The most recent application of this principle is found in the 2015 United States Supreme Court case Rodriquez v. United States. In that case, a motorist named Dennys Rodriquez was pulled over and issued a traffic citation for driving on the shoulder of the road. After the officer attended to everything relating to the stop, including checking the drivers licenses of Rodriguez and his passenger and issuing a warning for the traffic offense, he asked Rodriguez for permission to walk his drug-sniffing dog around the vehicle. When Rodriguez refused, the officer detained him for seven to eight minutes until another officer arrived and walked the dog around the vehicle anyway. The dog alerted the officers to the possible presence of narcotics, and a search of the vehicle uncovered a bag of methamphetamines. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the police extension of the traffic stop to conduct a dog sniff violates the Fourth Amendment shield against unreasonable seizures. The Court stated that a dog sniff is not fairly characterized as part of the traffic mission of the officer, noting that a dog sniff lacked the same close connection to roadway safety as the ordinary inquiries such as checking the license, determining whether there are outstanding warrants against the driver, and verifying the vehicle registration and liability insurance. "Officers cannot prolong a traffic stop just to perform a dog- sniffing drug search", wrote Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the court's decision in which Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan joined. "A seizure for a traffic violation justifies a police investigation of that violation—not more—and authority for the seizure . . . ends when tasks tied to the traffic infraction are or reasonably should have been completed." Applying the Rodriguez case to that of Sandra Bland, the inquiring about Ms. Bland's mood, asking her to extinguish her cigarette, and ordering her to exit the vehicle when she challenged this request cannot be fairly characterized as part of the traffic mission of the officer. Authority to seize Ms. Bland ended when the task tied to her traffic infraction end. Authority to seize Ms. Bland ended once Trooper Encinia wrote the warning and delivered it to Ms. Bland. At that point, nothing else needed to be said or done.

In addition to violating the Fourth Amendment rights of Sandra Bland, the actions of Trooper Encinia violated Texas law. The same Texas Code that says a person may not willfully fail or refuse to comply with a lawful order or direction of a police officer also states that a public servant may not—intentionally or with with knowledge that his conduct is illegal—deny or impede another in the exercise or enjoyment of any right, privilege, power, or immunity or subject another person to "mistreatment or to arrest, detention, search, seizure, dispossession, assessment, or lien." In the case of Sandra Bland, Trooper Encinia denied Ms. Bland the exercise and enjoyment of her rights to private property and of her rights to privacy by demanding that she extinguish her cigarette in her own car and detaining her for failure to do so. Smoking a cigarette in one's own car while waiting to be served with a citation is not illegal in Texas, and Trooper Encinia had no authority to interfere with this right. A public servant, according to the Texas code, also may not misuse "government property, services, personnel, or any other thing of value belonging to the government that has come into the public servant's custody or possession" with the "intent to obtain a benefit or with intent to harm or defraud another." In the instant case, Trooper Encinia misused his Taser gun, which was property of the State of Texas. Without reason to be apprehensive about his own safety or concerned with any flight risk Ms. Bland may have posed, there was no good reason for the trooper to threaten to "burn" Ms. Bland with his Taser stick. Texas State Trooper Brian Encinia broke the law. He violated the Fourth Amendment rights of Sandra Bland by detaining her longer than it was necessary for him to effectuate his traffic stop. He also violated the Texas Code as it pertains to the abuse of power of public servants.

As a practical matter, it was certainly in the interest of the self- preservation of Sandra Bland to obey Brian Encinia`s orders. My father used to warn my brother and I that "you can be right, dead right." But the unwise decisions of Sandra Bland do not excuse the vicious behavior a so-called public servant turned tyrant. A man who must have forgotten that his salary is paid for by the citizens of the great state of Texas. There are many sincere and well-meaning people who concede that the actions of Trooper Brian Encinia were legal, but who instead choose to argue that what Encinia did was unprofessional, inappropriate, or even morally wrong. The problem with this thinking is that police officers are often not deterred by righteous indignation or public pronouncements of their sins. Sometimes the misconduct of police officers can only be deterred by the officers being sued or prosecuted, resulting in the loss of the officer's liberty or property. From the facts of the instant case, it appears as if Trooper Brian Encinia acted both immorally and illegally. Not only does Encinia deserve public condemnation, but he should be sued or prosecuted, resulting in the loss of his own liberty or property.

Just click the red box (it's a button!) to pay the author

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

|