T.B. Macaulay as Conservative Classic

by Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Special to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

Essayist, historian, philosopher, poet, cabinet minister, parliamentary speaker, drafter of the Indian penal code, Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-59) was among the most eminent of the early Victorians. The first volume of his great History of England [Project Gutenberg] came out in 1848, the last completed volume after his death. It was an immediate classic. It sold in large and steady numbers into the 1930s. For style alone, the History deserved its status. Perhaps no other English writer has combined such clarity with such overpowering force. He demands his reader’s attention. Open the History — indeed, any of his works — at any page, and read for a while, and then try to look away: it needs great effort. But his achievement was more than style alone. Above all what he provides in the History is a compelling vision of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 — of its immediate causes and progress and consequences, and of its significance in the history of the human race.

His thesis is briefly stated. Alone among the great nations of Europe, England had preserved into the 17th century a free constitution from the middle ages. Elsewhere, the needs of defence had allowed the executive to raise large military forces, which had then been used to nullify every regular check on power. But our island status has never justified a standing army, and even the most despotic kings had been required to govern by consent according to the ancient forms. These forms came under threat by the early Stuart kings. The threat had been overcome, though with much bloodshed and the temporary loss of the Constitution. But the Restoration in 1660 had brought back not only the ancient monarchy, but the also the ancient forms. The struggle began again — the claims of absolute monarchy on one side, of limited government on the other. For much of his reign, Charles II had been on the defensive, tacitly or openly surrendering the claims of his father and grandfather. But a combination of judgement and luck allowed him to end his reign in much the position his grandfather had desired — easy finances and an irresponsible administration.

With his death in 1685, the struggle began in earnest. His brother James II was an avowed Catholic and admirer of France. His policy was to pack the administration with creatures dependent on him alone, and to procure the definite repeal of every safeguard that prevented him from having his will legally enacted and legally enforced. Granted success, he would have reigned over a nation enslaved to him, and have been himself enslaved to France.

But he failed in his policy. He moved too fast, and with too little regard to the opinion even of those whom it suited him for the moment to try conciliating. In his blind self-confidence, he raised a formidable coalition of forces against himself — a coalition of those who had hated each other with settled feeling during five generations. At last, he overreached himself. His leading enemies took advantage of his folly and set in motion a train of events that ended is his dying an embittered exile and the triumph of liberty in England. And the triumph of liberty in England meant its eventual spread to other parts of the world.

This was the Glorious Revolution. But what for Macaulay made it so glorious was its conservative nature. The Revolution brought profound changes in the practice of government in England. Parliament became the dominant force in the Constitution, nothing being possible without its consent, no government possible but by its preferred leaders. At the same time, justice was depoliticised, the courts made into the sure refuge of oppressed innocence. But considered in terms of outward appearance, the Revolution changed nothing. The expulsion of James was declared an abdication. William and Mary became joint monarchs not as leaders of a successful coup, but as the next in line of succession. The same offices, the same forms of action and address, the same impressions of legitimacy, were carried forward from one reign to another. The fact that a revolution stood between those reigns was, by general agreement, overlooked.

Macaulay’s status as a conservative is frequently denied. He was a Whig and a reformer. He denounced the Tories and Conservatives alike. In the loose party structures of Parliament in the 1830s, it was his eloquence that almost measurably produced the Commons majorities for the Reform Bills. But he was undeniably a conservative. He was as much in love with the English past as any of his opponents. But his was a rational love. The glory of our Constitution for him was that it had for many centuries reconciled liberty with order. Habeas corpus and trial by jury and freedom of the press were mingled with the picturesque survivals of the Constitution. The latter protected the former, and the former sanctified the latter. As a politician, he approached the crises of the early 1830 in exactly the same manner as he wrote the history of the 1680s. Despite its general excellence, the Constitution had its defects. Some of these might always have existed. But, with recent changes in the size and balance of economy and population, and with the growth of a more fastidious public opinion, they were no longer so lightly tolerated as they had been. For him, the question was not whether the Constitution ought to be reformed, but the manner in which reform should be made. “Reform that you may preserve ” he told the House of Commons in 1831. Accept reform now, while all else in the Constitution retains its hold on the public mind, and so can survive. Or see it imposed later by radicals whose haste and ignorance of the true facts of human nature will involve freedom and tradition in a common ruin.

Reform proved in the end less stable than the settlement of 1689. It was the prelude to a slow, destructive remodelling of the Constitution — a remodelling that has still to reach its end. We may not yet see the final shape of the new order that awaits us, but we can be sure that the faint outlines now visible would have utterly revolted Macaulay. He was the last and perhaps the greatest of the Whig writers, and he was a true conservative.

Reprinted from Sean Gabb's blog

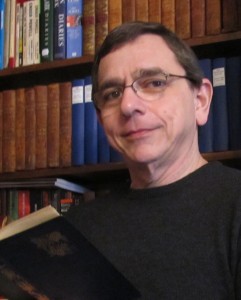

Sean Gabb is the author of more than forty books and around a thousand essays and newspaper articles. He also appears on radio and television, and is a notable speaker at conferences and literary festivals in Britain, America, Europe and Asia. Under the name Richard Blake, he has written eight historical novels for Hodder & Stoughton. These have been translated into Spanish, Italian, Greek, Slovak, Hungarian, Chinese and Indonesian. They have been praised by both The Daily Telegraph and The Morning Star. He has produced three further historical novels for Endeavour Press, and has written two horror novels for Caffeine Nights. Under his own name, he has written four novels. His other books are mainly about culture and politics. He also teaches, mostly at university level, though sometimes in schools and sixth form colleges. His first degree was in History. His PhD is in English History. From 2006 to 2017 he was Director of the Libertarian Alliance. He is currently an Honorary Vice-President of the Ludwig von Mises Centre UK, and is Director of the School of Ancient Studies. He lives in Kent with his wife and daughter.

Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Tel: 07956 472 199

Skype: seangabb

Postal Address: Suite 35, 2 Lansdowne Row, London W1J 6HL, England

The Liberty Conservative Blog

Sean Gabb Website

The Libertarian Alliance Website

The Libertarian Alliance Blog

Richard Blake (Historical Novelist)

Books by Sean Gabb

Sean Gabb on FaceBook

and on Twitter

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

![]()

AFFILIATE/ADVERTISEMENT

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy

found here. (Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)