Review of

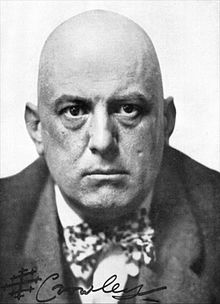

Crowley: Thoughts and Perspectives

by Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Special to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

Crowley: Thoughts and Perspectives, Volume Two

Edited by Troy Southgate

Black Front Press, London, 2011, 215pp, �10

ISBN 978-84830-331-7

It was late one afternoon, more years ago than I care to admit. I was working as an estate agent in South London, when an old beggar woman came into the front office. “Cross my palm with silver, Dearie,” she croaked in a strong Irish accent.

I glared at her from my desk. It was hard enough at the best of times to get potential clients or buyers to step through our door. The lingering smell she had brought of unwashed clothes and of the scabby, verminous body they no doubt covered was unlikely to help. “Get out!” I said, pointing at the door.

Her response was to shamble forward, a sprig of heather clutched in her hand. Thirty seconds later, she was steadying herself on the pavement. “You’re a wicked young man, ” she called, “and you’ll be dead in two weeks—you mark my words.”

“Piss off!” I laughed, dusting my hands together, “or I’ll set the police on you.” Back inside I set about looking for the tin of air freshener we kept for when the smell of tobacco smoke became too oppressive.

This happened a long time ago—much longer than the two weeks I was given. It did not determine my view of the occult. It does, even so, illustrate a view I have held since about the age of ten. During the past four centuries, we have seen the world in semi-Epicurean terms as a great and internally consistent machine. To understand it, we observe, we question, we form hypotheses, we test, we measure, we record, we think again. The results have long since been plain. In every generation, we have added vast provinces to the Empire of Science. We do not yet perfectly understand the world. But the understanding we have has given us a growing dominion over the world; and there is no reason to think the growth of our understanding and dominion will not continue indefinitely.

We reject supernatural explanations partly because we have no need of them. The world is a machine. Nothing that happens appears to be an intervention into the chains of natural cause and effect. We know that things once ascribed to the direct influence of God, or the workings of less powerful invisible beings have natural causes. Where a natural cause cannot be found, we assume, on the grounds of our experience so far, that one will eventually be found. In part, however, we reject the supernatural because there is no good evidence that it exists.

Forget that horrid old beggar woman. Look instead at the Nazis. It seems that Hitler was a convinced believer in the occult. He took many of his decisions on astrological advice. It did him no visible good. He misjudged the British response to his invasion of Poland. He was unable to conquer Britain or to make peace. His invasion of Russia, while still fighting Britain, turned his eastern frontier from a net contributor of resources to a catastrophic drain on them. He then mishandled his relations with America. So far as he was guided by the astrologers, I hope, before he shot himself, that he thought of asking for a refund. It was the same with Himmler. Despite his trust in witchcraft, he only escaped trial and execution by crunching on a cyanide capsule made by the German pharmaceutical industry.

Turning to practitioners of the occult, I see no evidence of special success. They do not live longer than the rest of us. However they begin, they do not stay better looking. Any success they have with money, or in bed, is better explained by the gullibility of their followers than by their own magical powers.

So it was with Aleister Crowley (1875-1947)—the “Great Beast 666,” or “the wickedest man alive.” He quickly ran through the fortune his parents had left him. He spent his last years in poverty. Long before he died, he had begun to resemble the mug shot of a child murderer. Whether his claims were simply a fraud on others, or a fraud on himself as well, I see no essential difference between him and the beggar woman who cursed me in the street. He had advantages over her of birth and education. But he was still a parasite on the credulity of others.

Nor can I see him as a thinker or writer of any real value. The book that I am reviewing does its best to claim otherwise. Its varied essays are all interesting and well-written. Anything by Keith Preston, who wrote the fourth essay, is worth reading. Mr Southgate has done a fine job on the editing and formatting. But I found myself looking up from every essay to think what a terrible waste of ability had gone into producing the book. Was Crowley a sort of national socialist, or a sort of libertarian? Was he a sex-obsessed libertine, or did he preach absolute self-control? I suspect all these questions have the same answer. The overall theme of the book is that he was a penetrating critic of “modernity,” and each of its writers—all, in my view, men of greater ability than Crowley—has done his best to reduce a corpus of self-serving nonsense to a coherent system of thought.

The truth, I think, is that, beyond a desire to impose on everyone about him, Crowley had no fixed ideas, but he was too bad a writer for this to be apparent. Take these examples of his prose:

We are not for the poor and sad: the lords of the earth are our kinsfolk. Beauty and strength, leaping laughter, and delicious languor, force and fire are of us…” [quoted, p.68]

The sexual act… is the agent which dissipates the fog of self for one ecstatic moment. It is the instinctive feeling that the physical spasm is symbolic of that miracle of the Mass, by which the material wafer… is transmuted into the substance of the body. [quoted, p.151]

In the second of these, he seems to show an influence of D.H. Lawrence—or of the sources that made Lawrence into another bad writer. In the first, he has certainly been reading too much Swinburne. I confess that I have not read anything by Crowley beyond the quotations in this book. Having seen these, though, I am not curious to look further. He was a nasty piece of work in his private life, and a victim of early twentieth century fashion in everything else.

But enough of Crowley. He is less interesting than those who think him interesting, and I will end this review by discussing them. There are, broadly speaking, two main strands in the opposition to the New World Order. Both agree about the emergence of a global ruling class that is both unaccountable to and hostile to the mass of ordinary people. Its political oppressions are mandated by a set of transnational and opaque institutions. It exploits us economically through several hundred privileged corporations, and through a fiat money system managed by half a dozen central banks. It discourages open discussion of its goals by spreading lies through the mainstream media and the schools and universities, and by imposing these lies through corrupted systems of law and administration.

Where these two strands disagree is the over cause of the New World Order. For one, it is the final result of the Enlightenment. Rationalism has stripped from us all sense of the transcendent. It has left us alienated and atomised, and unable to throw off our oppressors, or even fully to appreciate that we are oppressed. The answer is to go back to the pre-modern sources of wisdom—whether these are religious or ethnic, or frankly mystical. It is to cast off the mirage of equality, and to embrace natural hierarchy. For the other strand, the enemy is a counter-Enlightenment. This is rolling back all the gains made since about 1650—freedom of speech, freedom of trade, equality before the law, objective science, among much else—and replacing these with a restoration of the kind of system that has kept us, for much of our existence as a thinking species, from opening our eyes and looking properly about.

Now, I fall within this second strand. I believe that most philosophical and political wisdom is to be found in Epicurus, Sextus Empiricus, Bacon, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, John Stuart Mill, and the others of their kind. There are valuable insights beyond this progression. But these are the writers who asked the questions that matter. If their answers are often conflicting, they all dance close by the probable truth. The Enlightenment was our salvation. My only complaint about progress is that we have so far had too little of it.

I think there is a necessary connection between my philosophical and my political views—libertarians and scientific rationalists: if you are one, you need also to be the other. But the geography of the human mind is too complex for lines to be drawn where I think they ought to be. Not every scientific rationalist is a libertarian. Not every mystic or reactionary is an authoritarian. There are admirers of Crowley—and of Friedrich Nietzsche and Julius Evola, and of Hegel and de Maistre, and of many other thinkers for whom I have no time—who are libertarians in the only sense that matters. I see no point in exploring their motivations, as these are both mixed and continually shifting. But, if they do not share my opinions as I have explained them, they are undoubtedly committed to a radical scaling back of the established order, or to its complete overthrow. And they do not share my dislike of the New World Order because they are not in charge of it. Their traditionalist utopias are not mine. But they will not conscript me into them. They do not wish to stop people like me from living as we please.

The two strands of the opposition may never agree about the significance of Aleister Crowley, or about the primacy of scientific rationalism. But there is much else to discuss. In particular, there is much that each can gain from trying to understand the assumptions and concerns of the other. And there is much generally to be gained if conventional libertarians can reach out and give moral support to the decentralist tendencies within traditionalism. I may not be impressed by the subject of this book. But I am impressed by the ability of its writers.

Sean Gabb is the author of more than forty books and around a thousand essays and newspaper articles. He also appears on radio and television, and is a notable speaker at conferences and literary festivals in Britain, America, Europe and Asia. Under the name Richard Blake, he has written eight historical novels for Hodder & Stoughton. These have been translated into Spanish, Italian, Greek, Slovak, Hungarian, Chinese and Indonesian. They have been praised by both The Daily Telegraph and The Morning Star. He has produced three further historical novels for Endeavour Press, and has written two horror novels for Caffeine Nights. Under his own name, he has written four novels. His other books are mainly about culture and politics. He also teaches, mostly at university level, though sometimes in schools and sixth form colleges. His first degree was in History. His PhD is in English History. From 2006 to 2017 he was Director of the Libertarian Alliance. He is currently an Honorary Vice-President of the Ludwig von Mises Centre UK, and is Director of the School of Ancient Studies. He lives in Kent with his wife and daughter.

Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Tel: 07956 472 199

Skype: seangabb

Postal Address: Suite 35, 2 Lansdowne Row, London W1J 6HL, England

The Liberty Conservative Blog

Sean Gabb Website

The Libertarian Alliance Website

The Libertarian Alliance Blog

Richard Blake (Historical Novelist)

Books by Sean Gabb

Sean Gabb on FaceBook

and on Twitter

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

![]()

AFFILIATE/ADVERTISEMENT

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy

found here. (Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)