Britain: A World Power Again, if by Accident?

by Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Attribute to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

In London, and it seems elsewhere, the political and media consensus is that Britain is in its weakest international position since the late summer of 1940. Because we have a government of fools, we are at the mercy of the French, the Germans, the Spanish, and even the Irish. If we accept Theresa May’s Withdrawal Agreement, we become a colony of the European Union. If we withdraw our notice to quit, we suffer a different though probably equal humiliation. If we leave without any deal, we face some degree of economic disruption. Which of these options is worst may have some bearing on the lack of agreement within our political class—though which brings more or less advantage to any of the individual groups in Parliament also has much bearing.

I disagree with this consensus. I still regard Theresa May as our most incompetent and possibly treasonous Prime Minister in at least living memory. At the same time, we find ourselves with the greatest power to shape our destiny since 1938. It needs only minimal work from our diplomatic establishment, and minimal cooperation among our leading politicians. Let me explain.

I will not discuss the two first options before us. It would be a mistake to accept the Withdrawal Agreement. It would be a mistake to withdraw our notice to quit. We are left with the third option, of leaving without any deal. What outcome should we want from leaving in this manner? The answer is obvious. We should want several years of reasonably privileged access to the European Single Market—so that next April arrives without any disruption to our trade in goods and services. We should want an advantageous trade deal with the Americans, the Chinese and the Indians. We should not want to pay anything to the Europeans for this access. We should not wish to fall into the American orbit. We should not wish to make any concessions to the Chinese and Indians—on immigration, for example. These are maximal desires, and all of them can be had.

No one outside Europe likes the European Union. On the one hand, negotiating a trade deal with Brussels gives access to the largest single market in the world. On the other, trade deals come with many disadvantages. The Americans and Chinese would generally prefer to deal with the European countries as individuals. Giving full support to British withdrawal weakens the European Union at a time when it is already internally divided and therefore weak. The Russians are of little account economically, but they would rather not face a united Continent, able to interfere in places like the Ukraine. Their diplomatic help should be taken for granted. Because these countries are themselves not in agreement with each other, they can be played against each other. We should extract favours with limited reciprocity.

Faced with what ought to be an easy diplomatic coup, the Europeans should be brought back to the negotiating table, this time to agree something better than Theresa May has managed during the past thirty months of bungling. Everything was in place to achieve this in June 2016. Everything remains in place—even if achievement will now look more like accident than policy.

All it requires is some degree of cooperation in Parliament. Let us agree, for the sake of argument, that leaving without a deal would involve considerable disruption. No one is sure how much disruption there would be—but there would be some. But the risk must now be taken. Theresa May must be made to swallow her pride, and to start serious planning for a no-deal exit. This will involve some degree of state management of private business—perhaps temporary nationalisation, probably subsidies and tariffs and other trade barriers. The idea should be to cushion those sectors most likely to be damaged by spreading the costs. For the avoidance of doubt, my own preference is for limited government and free trade. However, bringing about the conditions in which these become possible may require messy compromises in the present. I suggest this observation to my fellow economic liberals in Parliament.

Jeremy Corbyn should play the statesman and offer moderate cooperation. His price can be a general election next autumn. He should have some chance of winning this, though the Conservatives—freed of their present split, and with a different leader—should also be less rudderless than they are. It goes without saying that those Conservative politicians who are now threatening to bring the Government down if no-deal becomes actual policy should close their mouths. Everyone who is calling for a second referendum should also shut up.

Will a pact be negotiated during the Christmas break? I hope it will, but am not holding my breath. If one is negotiated, we can go back to something like politics as normal. Our political and diplomatic establishment will at last have proved itself fit for purpose. If not, it will find itself in the same shaky position as the French Monarchy did in 1788. How this can or should end I prefer not to say, though I agree it would be an undesirable position.

So, here is the great test our governing institutions will face during the next fortnight. Are they really just about fit for purpose? Or must we all start thinking again? As in the August Bank Holiday Crisis of 1914, the whole decision lies in the hands of a few dozen named people at the top. The Eyes of History are upon them.

And let me add for my foreign readers, that what happens in London has considerable bearing on the viability and nature of the New World Order that emerged after 1991. Again, and now for reasons purely of length, I will leave this more implied than discussed.

Though I said I am not, let me confess—I am holding my breath. Those Eyes of History are very cold, and they have never been known to blink.

© 2018, seangabb.

Reprinted from

Sean Gabb's website

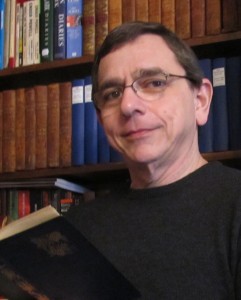

Sean Gabb is the author of more than forty books and around a thousand essays and newspaper articles. He also appears on radio and television, and is a notable speaker at conferences and literary festivals in Britain, America, Europe and Asia. Under the name Richard Blake, he has written eight historical novels for Hodder & Stoughton. These have been translated into Spanish, Italian, Greek, Slovak, Hungarian, Chinese and Indonesian. They have been praised by both The Daily Telegraph and The Morning Star. He has produced three further historical novels for Endeavour Press, and has written two horror novels for Caffeine Nights. Under his own name, he has written four novels. His other books are mainly about culture and politics. He also teaches, mostly at university level, though sometimes in schools and sixth form colleges. His first degree was in History. His PhD is in English History. From 2006 to 2017 he was Director of the Libertarian Alliance. He is currently an Honorary Vice-President of the Ludwig von Mises Centre UK, and is Director of the School of Ancient Studies. He lives in Kent with his wife and daughter.

Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Tel: 07956 472 199

Skype: seangabb

Postal Address: Suite 35, 2 Lansdowne Row, London W1J 6HL, England

The Liberty Conservative Blog

Sean Gabb Website

The Libertarian Alliance Website

The Libertarian Alliance Blog

Richard Blake (Historical Novelist)

Books by Sean Gabb

Sean Gabb on FaceBook

and on Twitter

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

![]()

AFFILIATE/ADVERTISEMENT

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy

found here. (Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)