|

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 609, March 6, 2011 "Fedbugs!" Attribute to The Libertarian Enterprise

Sometime during the late 60s or early 70s, I met an old, grizzled Vietnam veteran (he was just young enough to have missed the Korean War) who told me a story that would influence me for the rest of my life. I can't tell you exactly when it was, but it was before the advent of speedloaders. He had a men's wear shop downtown and kept clusters of six .45 Colt cartridges on shelves that didn't show, to reload the big Colt double action revolver he carried underneath his stylish jacket. But I have digressed already. At some point during the Southeast Asian unpleasantness, during a moment in which he didn't have a working firearm, he was confronted by a representative of the Viet Cong, who attacked him with a knife. The VC was smaller, and had a shorter reach, but he was fast, agile, and a better knife-fighter than my acquaintance. The only thing that saved him, he told me, was that his knife was heavier than the other guy's, and with each parry, the better knife fighter got worn down a little more.

Most of the blade weight is collected in the front end. I have a smaller Puma White Hunter that's been over the edge of the world with me and back. I always wanted a Waidblatt but could never afford one. (I almost had one in London, in 1976, from the Burlington Arcade, of all places.) At $915.26, they're still expensive, and fairly hard to find. But I'd gratefully accept one as a gift. Or a bribe. Make of it whatever you will, my dear "progressive" friends, I've always been oriented toward weapons, and toward tools that can be used as weapons. Maybe that's what comes of being the littlest kid in the class for most of my boyhood. Maybe it's just what comes of being very intelligent. In any case, when my fellow Scouts went to their sleeping bags shivering from the scary campfire tales they'd just been told, I crawled right in, wrapped my fingers around the handle of the hatchet I kept under my pillow (I still have it) and enjoyed a perfect night's sleep. Indirectly, that hatchet gave me a bit of an education. As an Explorer Scout, I was in charge of a herd of young scouts on a camping trip to Eglin Auxiliary #8 in the Florida panhandle. (Hurlburt AFB, where we lived, was Eglin Auxiliary #9.) Eight was where the First Air Commandos and other Special Forces trained in the early 60s. It was a huge forest on the banks of the Suwanee River of song and legend. On our trip, there had been heavy rain. The river was up over its banks, creating a swamp that started two hundred yards or so from the river proper. One morning I slipped away from camp to practice a little hatchet throwing against one of the gigantic trees that covered the area. One of our counsellors was a Commando who had earned his PhD by making primitive weapons by hand and learning to use them. He had taught me to throw a knife and a hatchet. I had made a few good throws when one of the kids caught up to me, and pleaded for a try. The tree was only ten yard away or so, and at least twenty feet wide, so I reluctantly agreed. Of course he missed the tree with his first throw, and I watched my precious and trusty companion plop into the swamp another twenty yards behind the tree. I picked my way out along big fallen branches until I finally saw my hatchet lying on one of them—right under an extremely annoyed-looking water mocassin in full threat display. I could see why people called them "cottonmouth"—the inside of his oral cavity looked like it was lined with white satin, just like a coffin. Most of his body was coiled up and rested on my hatchet. But I was sixteen years old, modeately stupid, and not about to give up my best weapon to some damn reptile. I shouted and stomped forward, surprising the snake, I think. Somehow, I snatched the hatchet out from under him, and was gratified—as I ran backwards along the logs faster than I'd even known was possible—to see him doing exactly the same thing. I may ask to be bufied with that hatchet. I had fixed-blade knives, too, of course, in addition to the fine, traditional BSA folder. I understand that's more than today's Boy Scouts are permitted, in the pussiocracy we've allowed them to build up around us. They were good ones, mostly German imports from the Base Exchange, but they were tiny and fragile by today's standards. I tried to improve them with a file and Dremel tool, clipping points and sharpening false edges, putting in sawteeth (with a checkering file) for cutting rope and tomatoes, but I couldn't make them any longer or heavier. My brother made me a medieval-style dagger out of a file for my birthday when we were young, with brass faucet handles brazed together for a heavy double guard, and it has a highly satisfying weight and reach.

The same reasoning applies to knives. I confess shamefacedly that I feel horribly guilty, saying all of these terrible things about what was once revered as the best fighting knife in the world. It stands beside the 1911A1 and the Garand. John Steyrs, in his epoch-making Cold Steel gets downright lyrical about it. I own two of them, myself, both by what I just learned is the original manufacturer, Camillus. One is stock, except for an inch or so of fine sawteeth I cut into the edge with a checkering file near the ricasso. I also modified the scabbard, something I do with almost all of my knives—but that probably deserves an article all by itself. The other I adapted for use as a bayonet for my little M1 Carbine, which solved the round handle problem nicely. (I have never understood why the militaries of various nations issue separate fighting knives and bayonets, when a single, properly-designed instrument would do very well and lighten the load by a pound or so.) But there you are; time marches on. The Brits replaced their cute little Sykes-Fairbairn splinter, and I keep something completely different handy, myself, today. I have long since retired my hatchet. But I know where it is. In the meantime, really big knives continue to contribute to my education and enrich my life. I would carry one now—especially a kukri—in preference to any axe, large or small, that I was offered. But that's a story for another time. Author's note: manufacturers and purveyors of knives who wish to see their products reviewed by this column are invited to write to me at [email protected] for mailing details. In all cases, merchandise will remain the property of the author. Those items that I especially like may end up in the hands of the characters of my novels.

TLE AFFILIATE

|

I don't know what the VC had—almost certainly something

improvised from a machete or a bandsaw blade. The guy telling the

story was armed with a Gutmann Cutlery Puma "Waidblatt" (it means

"broad blade"), one of the biggest outdoor knives available at the

time (along with the 6" Buck "General"), 8 2/3 inches long (overall

length is 13 inches) with a good, stout blade thickness of 5/8 of an

inch.

I don't know what the VC had—almost certainly something

improvised from a machete or a bandsaw blade. The guy telling the

story was armed with a Gutmann Cutlery Puma "Waidblatt" (it means

"broad blade"), one of the biggest outdoor knives available at the

time (along with the 6" Buck "General"), 8 2/3 inches long (overall

length is 13 inches) with a good, stout blade thickness of 5/8 of an

inch.

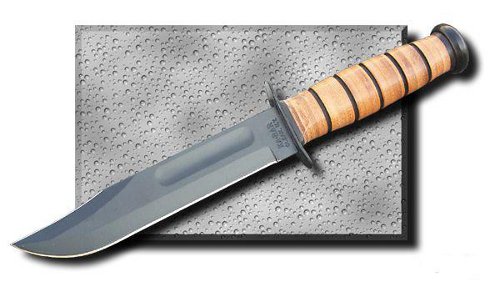

These days, for me, big knives properly start at around eight

inches. (Don't scoff; a former editor of mine believes big knives

start at twelve inches.) I was a fan of the traditional Marine Corps

Ka-Bar for years, but the handle is round, making it hard to know

which edge is up in the dark, and with a 7 inch blade 5/32 of an inch

thick, it's too short and too light. It weights two thirds of a pound.

I know that's a plus to guys who have to lug a 60-pound pack, but it's

the wrong place to make economies. An old friend of mine used to say,

"Weapons and ammunition are not heavy. Food is heavy. Spare socks are

heavy."

These days, for me, big knives properly start at around eight

inches. (Don't scoff; a former editor of mine believes big knives

start at twelve inches.) I was a fan of the traditional Marine Corps

Ka-Bar for years, but the handle is round, making it hard to know

which edge is up in the dark, and with a 7 inch blade 5/32 of an inch

thick, it's too short and too light. It weights two thirds of a pound.

I know that's a plus to guys who have to lug a 60-pound pack, but it's

the wrong place to make economies. An old friend of mine used to say,

"Weapons and ammunition are not heavy. Food is heavy. Spare socks are

heavy."