|

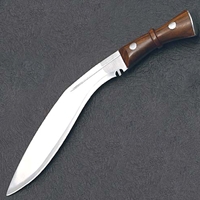

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 611, March 20, 2011 "They are deliberately destroying America" Attribute to The Libertarian Enterprise Growing up in the military, in the shadow of World War II, I saw lots of strange and fascinating things around the neighborhood and in school. If the same rules had applied back in the 1950s that are in force today, all of my friends and I would still be in prison under official "zero tolerance" prohibitions against anything that was interesting or fun. We swam in an ocean of military surplus back then, GI canteens, mess kits, tools and utensils, every kind of canvas bag imaginable. Most of it was American, some of it was British or German or Japanese. One item I saw being brought to school time and time again, was a very peculiar knife. It was large, heavy, and usually came in an awkward leather-covered wooden scabbard with two tiny auxiliary pieces. Oddest of all, the long broad blade was bent forward somewhere in the middle, and sharpened on the inside of the curve. The or spine back was thick and heavy. At the time, it seemed ugly and useless, and it could be had for next to nothing in pawn shops and surplus stores practically everywhere. We called it a "Gurkha knife". As military brats, every one of us knew all about the legendary Gurkhas, of course, tough, wiry little men from Nepal—we weren't exactly certain where Nepal was—absolutely fabled for their indomitable courage and unwavering ferocity in battle. Later on, the weapons guys among us learned that their famous knife is called a "kukri". This was Nepal's standard-issue military knife that my schoolmates were bringing to school. It remains so today. The Gurkhas were on our side against the Japanese in Asia (very heartening for Americans and Brits, very disturbing to the Japanese who were rightly terrified of them) and one hoped that the presence of their fighting hardware on American soil was a result of GIs swapping iron, as they always do, rather than battlefield salvage. We showed it going on in Roswell, Texas, not just a kukri for a Bowie, but a Sten or an Enfield for a Winchester.

My first kukri was a surprise gift many years ago that I would never have bought for myself, but which I treasure to this day. It's not a weapon, nor is it really a tool, but a ceremonial instrument for striking off the head of a young bullock, supposedly to obtain good luck. The knife, if you can call it that, is well suited to the task. The blade is two and a half inches wide and 29 inches long, three quarters of an inch longer than my katana, and only three and a half inches shorter than the Victorian Wilkinson cavalry saber that my wife and I stepped over at our wedding. The giant kukri blade is a quarter of an inch thick. The whole thing weighs about as much as a light rifle. The blade is obviously hand forged with fullers and a peculiar rippling pattern, then highly polished and decorated along the spine and on the ricasso by stippling in scroll patterns. The handle is made of buffalo horn decorated with a silver-colored ferrule, bands and pins, and an embossed metal pommel cap shaped like an African lion's face. It says it was made in India. It seems that nearly all of my kukris were made in India, where they're used every day, just like in Nepal. A typical one of them has a blade 13 1/2" inches long, extremely plain, and lacks any fullers or "blood gutters" as we kids used to call them. It's stamped with a "broad arrow", which I always thought denotes military use. It also lacks the ceremonial "kauda", a pair of notches at the base of the blade for which there seem to be as many explanations as there are explainers. It has a perfectly horrible scabbard that looks like it was sawn from one of the old tea chests Brits used to use instead of cardboard boxes. One thing you can count on absolutely: the legend you hear about never sheathing the big bent knife without first drawing blood is nonsense. If you're planning to chop kindling or cut up a goat, or perform similar mundane chores with it every day, you can't afford the Bandaids. Or the blood-loss. This is the knife I used after that storm, and my neighbors all envied me. It can slice through a two-inch limb in a single swing, and doesn't require a chopping block to work against. It is safer and handier than a chain saw (my opinion; the damned things scare me). The steel—most kukris, I have been informed, even those produced for military contracts, are fashioned from the leafsprings of old trucks—is a little toward the soft side. It takes a razor edge, but has to be touched up frequently with a stone or file kept handy in one's pocket. The little handle on the full-tanged blade is a pair of small hardwood cylinders, attached with fat rivets through the tang. It's way too small for my hand. In the end, wishing to avoid blisters, I wrapped the grip with hockey tape in the time-honored manner, and it works just fine. If I needed to chop down a tree, despatch a chicken or a pig, or even go in harm's way with that big knife. I wouldn't complain. Not much, anyway.

When they arrived, I realized I'd never seen a kukri that was brand new before. They're both beautiful. The larger of the two has a fuller on each side of the blade and a proper kauda at the base. The traditional spindle-shaped polished hardwood handle-halves are fastened onto the full tang with two big rivets and a plain steel butt cap.

The scabbards are of wood, covered in thin black leather, with almost perfectly useless "frogs" for carryng them on a belt. (Notice that the Singapore cop's knife is in some sort of metal bracket.) Sheaths and scabbards are an ancient and continuing problem for most knife makers, and the subject deserves a column all by itself. Both came with the traditional pair of small auxiliary tools, the karda, a miniature blade, and the chakmak, a sort of steel or sharpener. Oddly, the large knife has two kardas, while the small one has two chakmaks.

The knife is a bit lightert than the others, entirely of modern construction, with a sophisticated steel alloy blade, coated in sort of black Teflon-like material. The handle is a modern shape—with a nod to the traditional spindle—made of Kraton or something like it. Some pundits I know don't care for rubber handles in the field, but I find them comfortable, warm to the touch, and usable for much longer periods. The leather scabbard is lighter, too, a well thought-out design. I've used this knife—which Cold Steel calls a "kukri machete"—for more yard work than any other, and have come to like it very much. I left it out in the weather for a few days on one occasion; while the scabbard is a little worse for the wear—rain and sun—the knife is just fine. It's easy to sharpen and stays sharp, not being made from a truck leaf spring. It would make a formidable weapon. When I started writing Roswell, Texas with Rex May, I had intended to make a great deal more of the juxtaposition, arising from the plot, of the Texican Bowie knife and the Gurkha kukri (it's a long story if you haven't read the graphic novel); I had even worked out a little logo, the two weapons crossed over one another, for the spaces between chapters, but the conceit proved difficult to maintain in pictorial format, and I have no idea when, if ever, we'll get back to the text novel. Still, I haven't given up altogether. When I return to Ares, the story of an accidental rebellion among Martian colonists, aided by a handful of Pallatian volunteers, against a punitive expedition from Earth by United States (of East America) Marines, the first segment I'll write will be a knife duel between a Marine and one of the Pallatians. The young female Marine lieutenant—my readers already know her later in her life as Julie Segovia Ngu, Llyra and Wilson's grandmother—will carry an ancient Confederate D-guard Bowie knife. Her opponent—Emerson and Rosalie Fraser's eldest son William—will have a kukri. Should be interesting. Author's note: manufacturers and purveyors of knives who wish to see

their products reviewed by this column are invited to write to me at

Giant kukri guy's url

www.random-abstract.com/kukri

TLE AFFILIATE

|

There's a nice photograph of a Singapore city cop in Wikipedia (a

member of a Gurkha contingent, it says here) carrying a kukri on his

belt. The entry says that you can find a kukri (variously spelled

"kukri", "kukhri", or "kukuri") everywhere in Nepal, in kitchens,

barns, worksheds, and woodlots. Having spent many hours with one in my

hand, cleaning up after limb-breaking snowstorms, I can attest that

it's an excellent tool for many tasks, a proud symbol of the Nepalese

nation.

There's a nice photograph of a Singapore city cop in Wikipedia (a

member of a Gurkha contingent, it says here) carrying a kukri on his

belt. The entry says that you can find a kukri (variously spelled

"kukri", "kukhri", or "kukuri") everywhere in Nepal, in kitchens,

barns, worksheds, and woodlots. Having spent many hours with one in my

hand, cleaning up after limb-breaking snowstorms, I can attest that

it's an excellent tool for many tasks, a proud symbol of the Nepalese

nation.

Once I discovered how useful kukris could be, I decided I wanted

one of the military type I'd seen throughout my misspent boyhood.

Thanks to Atlanta Cutlery, I purchased an official 12 inch regimental

knife, and a 9 3/4 inch officer's model, both manufactured by the

outfit—India's Windlass Steel Crafts, about which I will have a

great deaL more to say in the future—that makes them for real live

Gurkhas.

Once I discovered how useful kukris could be, I decided I wanted

one of the military type I'd seen throughout my misspent boyhood.

Thanks to Atlanta Cutlery, I purchased an official 12 inch regimental

knife, and a 9 3/4 inch officer's model, both manufactured by the

outfit—India's Windlass Steel Crafts, about which I will have a

great deaL more to say in the future—that makes them for real live

Gurkhas.

The smaller officer's knife has the same fullers and kauda, Its

handle is made of buffalo horn, with a brass bolster or ferrule at

blade end, and a brass plat at the other. This knife appears to have a

rat-tail tang, as it emerges through th end cap where it is peened

down.

The smaller officer's knife has the same fullers and kauda, Its

handle is made of buffalo horn, with a brass bolster or ferrule at

blade end, and a brass plat at the other. This knife appears to have a

rat-tail tang, as it emerges through th end cap where it is peened

down.

Neither last nor least is the most useful crooked knife I have

found so far is the Cold Steel Kukri. Mine is sort of a compromise

between the two models presently offered. It has a 12 inch blade with

a shape almost identical to that of the military knife discussed

above.

Neither last nor least is the most useful crooked knife I have

found so far is the Cold Steel Kukri. Mine is sort of a compromise

between the two models presently offered. It has a 12 inch blade with

a shape almost identical to that of the military knife discussed

above.