|

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 689, September 23, 2012 "Almost everybody believes that other people's lives, and the products of those lives, are theirs to take away and use in any manner that strikes them as desirable."

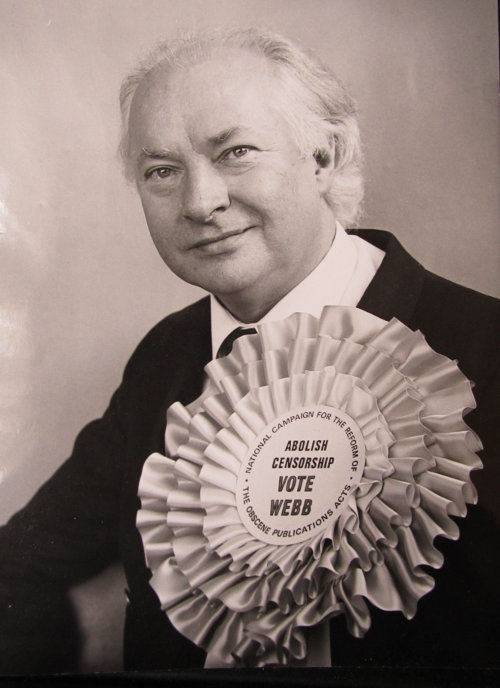

Obituary Attribute to L. Neil Smith's The Libertarian Enterprise David Alec Webb, wit, raconteur, well-known actor on stage, screen and television, and tireless—and ultimately successful—opponent of the laws against pornography, died on the 30th June this year, at the age of 81. The son of a car worker, he was born in Luton in 1931. He attended Luton Grammar School, where he did well academically and became Head Boy. After national service in the Army Education Corps, where he became a sergeant, he got a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA). From here, he embarked on a long and successful career that began on the West End stage, but soon migrated to television. He was a prominent character in the early days of Coronation Street. Worried about the dangers of typecasting, he soon moved on, and, between the 1960s and the beginning of the present century, made well over 700 appearances in television programmes. These included Upstairs, Downstairs, Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased), Tales of the Unexpected, Doctor Who, and The Avengers. He also found time for the cinema, appearing in, among much else, The Battle of Britain. In a profession which, notoriously, has an unemployment rate of 80 per cent, he was never out of work. He was at one point so committed to television, and so prolific, that he was mocked by some of his RADA friends as a "Telly Tart." His response was a magisterial wave of the arm and the explanation: "On the telly, dear boy, you don't have to get it right first time, and the repeat fees mean you'll never run out of gin." He was right. Even today, it is an unusual week on ITV3 when David Webb is not seen and credited in one of its many repeats from the golden age of British television. Popular, despite his success, in a profession somewhat given to jealousy, David was elected to the Council of Equity, the actors' trade union. Among his wide circle of close and longstanding friends was the comedian Frankie Howerd, whose lover he was for several years. As well as an actor, though, David was also an outspoken libertarian; and it may be for the impact he had as a libertarian on law and policy in England that he will be best remembered. In 1976, he founded the National Council for the Reform of the Obscene Publications Acts (NCROPA), and began his long campaign against the prudes and censors of every political and religious complexion. In those days, the laws against pornography were, in their principle and intent, very clear. For those on the inside—which included David—who had the right friends, or knew the right officers in the Metropolitan Police, there were no restrictions. For everyone else, it was "No Sex, Please: We're British." Pornography was defined as anything a jury could be nagged into agreeing had a tendency to "deprave and corrupt." This meant, for example, no open crotch shots for women, and no "stiffies" for men. On this latter, judges and learned counsel could spend days, and even weeks, solemnly considering whether a particular male organ was naturally large, or was supported by a convenient length of tubular steel furniture, or was illegally tumescent. Against this unfairness and absurdity, David stated his own principle to anyone who would listen: "So long as it's by and for consenting adults, nothing should be forbidden." David used the circle of friends and contacts he had made as an actor to ensure that NCROPA could not be ignored. He attracted public support from Clement Freud MP, and funding from the organised sex industry. For a quarter of a century, he lobbied the Government while trying to gain support in the media. He also engaged in direct litigation when he thought it useful to bring test cases into court. It was a long and often frustrating struggle. In those days, hypocrisy about sex was almost universal, and the leading politicians of all parties were united in their public condemnation of "filth." In 1978, he even earned a personal condemnation in a Sun editorial— just across, of course, from its page three photograph! He faced all this with good humour tinged with contempt. Once in a studio discussion programme, someone accused him of promoting sexual violence against women. "Don't be silly!" he snapped. "I've been in more comedy than you've had haircuts." To the applause of the audience, he continued: "It's had no effect on the amount of laughter you see in the streets." Of course, the condemnation was often only in public. In 1981, David led a delegation to see William Whitelaw, the Home Secretary of the day. Whitelaw was completely sympathetic in private. But he flatly insisted that he could never get reform of the "porn laws" through the Cabinet or through Parliament. In 1983, David stood for Parliament as a freedom of expression candidate. With his characteristic boldness and lack of respect for the great, he stood in Finchley against Margaret Thatcher. The Prime Minister was not amused—it is even possible that David's challenge strengthened her determination to push through the Video Recordings Act the following year. While campaigning, though, he struck up a long and convivial friendship with Carol Thatcher, the Prime Minister's daughter. Success in the campaign came unexpectedly but all at once. Though happy to fund him, David's supporters in the sex industry had always been careful to avoid open challenge to the law. Then, in 2000, he managed to procure a commercial video which was rejected by the British Board of Film Censorship (BBFC). David pushed the makers into appealing to the Video Appeal Committee—a body set up to comply with the Human Rights Act 1997. The VAC passed the video. The BBFC then appealed into the High Court. Its argument was that it was protecting a "vulnerable minority" which might be unbalanced by exposure to explicit material. The High Court ruled this "disproportionate" under the European Convention on Human Rights. The judgment was so strongly worded that the BBFC had no choice but to cave in and liberalise its guidelines defining obscenity. It even softened its name to the British Board of Film Classification. One of the benefits of this judgment was that the Customs and Excise and the various police forces in England and Wales adopted these new guidelines for themselves, thereby giving up on their own, often far stricter definitions of obscenity. It was a settlement of the issue that suited all parties. The increasingly ridiculous and—because of the Internet—increasingly unenforceable censorship of sexual expression largely fell to the ground. At the same time, no elected politician had to run the gauntlet of Daily Mail and pressure group disapproval. The changes were quietly accepted. In this respect, while the Blair Government cannot be regarded as friendly to civil liberties, England became a slightly freer country. In his later years, David was often told that his campaign had been a waste of time—that the Internet had done more to liberalise the law than all his campaigning. His reply was a shrug and: "By 1967, too many of us were openly buggering each other for the law to be strictly enforced. Does that mean campaigning for that year's Sexual Offences Bill was a waste of time? Just because a law is unenforceable doesn't mean it can't be rolled out now and again to destroy a few lives. I did my bit to make this country a better place. I'm not disappointed by the result." In private life, David was a grand, convivial character, who loved good company, good food, good drink, and classical music. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer early in 2012, and its progress was so rapid that he had no time to stop being the man his friends had all known and loved. He faced his end with the equanimity of a true follower of Epicurus. He died peacefully and in his sleep at Trinity Hospice in Clapham. He was 81. His funeral was at Mortlake Crematorium on the 17th July 2012. As might be expected, it was a diverse and not wholly joyless event. He is survived by his sister Pam and his goddaughter Nikki. Was that worth reading?

TLE AFFILIATE

|