|

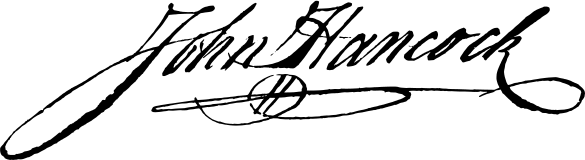

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 776, June 22, 2014 Every man, woman, and responsible child has an unalienable individual, civil, Constitutional, and human right to obtain, own, and carry, openly or concealed, any weapon—rifle, shotgun, handgun, machinegun, anything—any time, any place, without asking anyone's permission. Attribute to L. Neil Smith's The Libertarian Enterprise Over the years, I've written many an unflattering thing about actors, as a class, especially about their intelligence, or lack thereof. It's hard to understand how anyone can get it all wrong so consistently. Now, after several weeks of trying to be an actor myself, I can tell you something else about them: what they do isn't easy; even if they happen to do it poorly, it's a bit of a miracle they can do it at all. Actors, as a class, are neither stupid nor lazy. On the contrary, they are some of the hardest-working people on the planet. I can't remember a math class in college that was as hard as acting, and I now believe they use up all their available intelligence doing what they do, and don't have lots left over for other considerations, which may account for the foolishness of their stated views on collectivist economics, "social justice", banning gun ownership, global warming, animal rights, and a great many other silly things they profess to believe. Like someone else we know, half their brains are tied behind their backs. If they applied the same amount of mental energy to history and politics as to memorizing a script, they'd be radical libertarians. (TV actors may be an exception to this observation; they use cue cards and teleprompters and still can't think their way out of a wet paper bag.) How do I suddenly know all this? Well, what now seems like a year ago (but was probably more like eight weeks) my daughter cast me in her independent production of 1776, a brilliant, lively, and moving musical romantic comedy about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. I was proud of her. Just as I had decided, entirely on my own, without anybody's permission, to be a novelist, she decided to be a producer. That is the very quintessence of the America I love and mourn. I was (and to some extent remain) John Hancock, President of the Second Continental Congress, technically, the first President of the United States, and staunch advocate of separation from Britain. My lovely and talented wife (the producer/director's mother) Cathy L.Z. Smith, played Mary-land delegate Samuel Chase. Our lovely and talented daughter, professionally known as Giovanni Martelli (long story) not only produced and directed, but played the leading character, John Adams. Before you ask, yes: there's a great deal of gender cross-casting in local theater (not enough guys are interested), and several other ladies helped portray the first congress-critters. Gianni was informed by "older, wiser heads" that she couldn't get away with playing John Adams. Then again, the same sort told her 1776 is too ambitious for a first project. As usual, "older, wiser heads" were wrong. She was brilliant as John Adams, and, over the weeks, knitted a random gang of acquaintances and strangers into a stage family that was a thrill to be a member of and work with from the first "Sit down, John!" to the final bell that tolls, ending the play at the actual signing of the Declaration. Me, I was damned lucky to get away with it. From the very first read-through, conducted in a "stolen" classroom on a local college campus, I had trouble memorizing lines, and even worse, remembering cues. The only other time I'd acted on a stage was in high school, when I played a minor character in Anastasia and concluded that acting was not my cup of tea. I was accustomed to entertaining big audiences when I had a guitar to hide behind, but that seemed very different. I never did learn all my lines and cues for 1776, and was reduced to reading them, instead. But I read pretty convincingly, Hancock spends most of the time immobile behind his Presidential table, and as I say, I got away with it. I watched other people, most of them a third my age, wrestle with various aspects of what we were doing. Some had to learn to carry a tune better (or at all). Some had trouble with lines, like I did. Some couldn't "project" beyond a mouse-whisper when they began. Words came up they didn't know how to pronounce. There was a touching struggle for two young people, unknown to one another only days earlier, to handle their first passionate and prolonged stage kiss gracefully. Along the line Gianni had to teach a bunch of big guys to dance the minuet—where the hell did she learn that? In the end, we put our show on in a big, beautiful blue-carpeted room of the local Masonic lodge, built, I heard somewhere, in 1889. The Masons charged us fairly and were extremely kind. I had to shave my beard off, but I got to wear 18th century clothing, which I like very much. (The wigs I can do without.) One thing I do know how to do is sing. I got to perform four solo lines and I would do it all over again just for that. I plan to do some reading and consulting about stage memory and then take another whack at it if I'm offered the chance. What amazed me most of all was how gracefully and professionally my daughter handled 20-odd individuals of greatly diverging ages and experience. She occasionally raised her voice, but everybody loved and respected her at the end, which is an achievement in itself. She also found all the props and made the costumes, with a little help from her friends. She's been in a handful of local plays put on by others, and was a figure-skater for ten years. But how she came to do this, and to acquit herself so astonishingly well remains a delightful mystery to me. In the beginning, I found the rehearsals three days a week exhausting. I had let myself fall out of shape, and I paid dearly. Sometimes I found myself nodding off in the middle of the play. But with time, I grew stronger, and although I had to sleep all day for a week afterward, I'm not such a mess any more, and I have my daughter to thank for it. Regrettably, we have no recordings—the company renting us the rights forbids it—so I can only describe it in the hope you will believe me. There are photos on FaceBook at Independency Productions. I'll be writing about this experience again. Though penned by obvious liberals, the play contains great wisdom and is a thing of beauty. Of course you can always rent the movie.

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

|