|

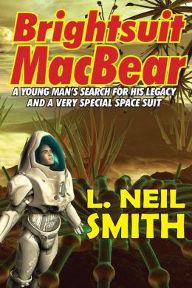

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 798, November 23, 2014 There is no one in charge. There are only lies. Attribute to L. Neil Smith's The Libertarian Enterprise AUTHOR'S NOTE: This novel was first published 26 years ago and is about to be reissued—like Brightsuit MacBear—by my friends at Phoenix Pick. It is the second part of a "young reader" series of seven books I'd planned to evoke the spirit of the Robert A. Heinlein "juveniles" all of us '46ers grew up on. The difference is that, while these books stand on their own, together they tell an eighth, overall story. The original publisher lost interest after two books, but I've now been given the go-ahead on the remaining five. So if you're looking for a good, principled, but exciting book to give your kids, you grandkids, your nieces and nephews this holiday season, full of new ideas and colorful characters, look no further than Taflak Lysandra or Brightsuit MacBear, both available in paperback or electronic format from Amazon and places like that. And remember, there's more to come. It was one of those frozen moments. "I told you to stand where you are!!" the girl with the military pistol shouted. "Put your hands up!" Two of the three on the dock complied, an annoyed and grumbling Grossfuss adding several feet to his already impressive height; Howell, as might have been expected, with all four feet on the dock, the mechanical arm between his shoulder blades raised to the vertical. Elsie stood with her elbows near her hips, her forearms level, her twin Walther Electrics held at a subtle angle that would cross their lines of fire—paired and furious streams of ultravelocity trajectiles—at the solar plexus of the individual who threatened Elsie's voice was quiet and firm: "Drop your weapon." "You drop yours!" "Well, whaddaya know?" laughed Grossfuss, "A Majestan standoff . Good work, kid, I didn't even see y'draw." The girl aboard the subfoline might have been attractive, Elsie thought, if it hadn't been for her dirty and bedraggled clothing, her tangled hair, and the dark circles under her eyes. Something serious was wrong with her, however, for the muzzle of her big ominous looking handgun—an actual chemical-powered firearm, if Elsie knew her history—made figure eights as her hands shook. Grossfuss spoke again, his voice as level and calm this time as Elsie's. "It's all right, Goldberry, these here are the vessel's owners. You can relax, now." "Hunh?" The girl leaned forward, peering at Grossfuss, suspicion and confusion battling for domination of her face, exhaustion serving as a sort of referee. "At ease, Leftenant MacRame." The yeti put an edge in his voice: "Stand down! Dismissed! For a moment, Elsie thought the girl was going to shoot. Then, as weary comprehension won an upset victory over her features, the weapon's muzzle dropped. She collapsed in a sprawling heap across the curved hull of the Victor Appleton. Elsie holstered her Walthers. She and Grossfuss hurried down a nearby ladder to a small, unbristled area at the subfoline's bow that served as its upper deck, with Howell—his four feet something of a disadvantage, where ladders were concerned—following. Elsie reached the older girl and knelt, feeling for the pulse at the base of her throat—it was strong and regular—and trying to remember her first aid. I take it, then, that you know this person?" Howell asked the yeti, catching up. Grossfuss looked down, nodding his great head. Yeah, that's Leftenant Commander Goldberry MacRame, or so she says, late of the Antimacassarite Navy. Her screwmaran-of-war got sorta eighty-sixed in that big tussle up north, which put her on the beach an' outa luck. I promised her a few silver ounces t'watch the Victor Appleton , here—too many strangers in port—while I went t'look for you." Howell considered this. "Later I'll ask you what in Benjamin Tucker's name a screwmaran is. For now, I'd be satisfied knowing how she got down here to the Pole, when, according to the reports, the battle happened on the equator only yesterday, six thousand metric miles away." To be certain of his facts, Howell had checked with his cerebrocortical implant—which performed other functions besides enhancing his intelligence—tuning it to one of the local news services. The conflict was still being given what another medium would have called "front page" treatment. His memory had been correct. "It would have taken the speediest hovercraft I'm familiar with," the coyote estimated, "at least all night to make such a trip. And I believe the colonists don't have aerocraft. How do you suppose she got all the way down here?" Grossfuss shrugged. "Dunno," replied the yeti, scratching his head. "Claims she got concussed in the dustup an' don't remember a thing between that an' when I put her on the payroll." Elsie looked up from the unconscious Goldberry MacRame, her nose wrinkled with annoyance. She gave the nosepiece of her glasses a tap with her forefinger to push them back into place. "While you two detectives figure out her itinerary, maybe you can help me get her in out of the sun and treated for shock, exhaustion, and probably malnutrition." She turned to her father. "How do we get inboard—the usual way?" Howell blinked. "Quite right, my dear, yes. I"m sorry." Again the coyote issued certain mental commands to his implant, this time to emit a short-range signal called a key code, the same means by which any Confederate might have unlocked his hovercar or the front door of his home. His effort was rewarded with a yelp from Elsie as the deck beneath her knees began to absorb her, just as the restaurant table had earlier absorbed the fly. It was also, of course, a reversal of the process by which his food had come to the table. Elsie, as familiar with this method of transportation as she was with walking, had been startled only by its suddenness and the location of the "door" beneath her. Inch by inch, the molecules of her body interpenetrated those of the hull. Some help from Grossfuss was required, folding the helpless Majestan officer's legs at the knees and tucking her arms at her sides. Together, he and Elsie let the permeable surface lower them and the unconscious girl into the cool dark of the subfoline's interior, where it became a deck beneath their feet (the ceiling closing in over their heads), and, following Howell's directions, they passed in a more conventional manner—walking under their own power—through the control area and the small dining facility and galley, to place Goldberry MacRame in one of the half dozen closet-sized cabins intended for passengers and crew. "An Antimacassarite, you say?" Howell's auxiliary arm held the primitive cartridge pistol before his eyes, turning it over for examination. He'd returned to questioning Grossfuss as soon as his daughter had seen to the colonial girl's needs—which had included a sponge bath and the business end of a glucose drip inserted into one limp, unresisting arm—and tucked her into the bunk under an extra blanket. The three sat in the dining area, where Grossfuss had let one of the chairs dissolve into the deck because its available range of sizes were all too small for him, and sat, instead, in the space it had occupied. Even so, he was still taller than Elsie. Howell had found makings and machinery for coffee and brewed a pot. Now three steaming mugs—two steaming mugs and a steaming mixing bowl for Grossfuss—rested on the table before them. The Himalayan nodded. "I reckon you know there was two old- fashioned nation-states here on Majesty when the first Confederates arrived. Still are, for that matter—Antimacassar an' Securitas by name." "Yes," the coyote answered, "with regressive cultures and technologies, as is usually the case with the First Wave. So far they've climbed back, after nobody knows how many cycles, to relatively sophisticated mechanics—gear trains, differential hoists—but neither to heat-engines nor electricity, as yet." "Prob'ly coulda had steam engines, if slaves wasn't so cheap an' easy t'come by." "I see." Howell's voice was grim. "Go on." "Natcherly," the yeti continued, "they been sluggin' it out with each other—barrin' occasional unavoidable outbreaks of peace—for the last several centuries. What else is nation-states for, I ask you? What I don't understand's the taflak gettin' involved. They''re usually smart enough t'stay well out of it." "I gather," Howell inquired, "that their participation in the recent battle is unprecedented?" The giant primate nodded, taking a quart-sized sip of his coffee. Listening, for the moment without comment, Elsie shook her own head. Her world, although she was in no position to realize it, had always been built inside out. Within the fuzzy but ever-expanding borders of the Galactic Confederacy, peace, personal freedom, and prosperity predominated. Outside those borders, thousands of petty, primitive empires and dictatorships—like Antimacassar and Securitas—resisted its expansion to the best of their limited ability. This might have been easier to understand had the Confederacy possessed anything resembling a central government, bent on interstellar conquest, but it didn't. The Confederacy consisted, in the main, of scientists, explorers, and merchants, out to profit (this was no less true of the scientists and explorers, in their own way, than of the merchants) by trading whatever they had too much of, for things that other beings produced in surplus, guaranteeing satisfaction all around. Enjoying, in her absent, thoughtful way, Howell's conversation with the giant mechanic, Elsie poured herself another cup of coffee, warmed her father's, and went to start another pot for Grossfuss. From a different perspective, of course, the Confederacy's lack of authority and territorial ambition, its interest in trading goods and information, rather than missiles and death rays, were the very reason its expansion was resisted. Throughout the sad, violent history of her native planet, those rare individuals who valued liberty above all else had always been forced to flee—most of the time westward—across the battle-scarred face of the globe, in an attempt to escape either from outright tyranny or from cultures they regarded as cramped and "overcivilized." All this had changed, however, with the advent of what at first had been the North American Confederacy, the concrete political expression of a logical process which had led from Thomas Jefferson's observation that "The government that governs best governs least" to the realization that the government which governs least is no government at all. As this realization began spreading, those individuals (not quite so rare) whose livelihood depended on stealing what others had labored to create—burglars and bureaucrats, pickpockets and politicians—reacted with alarm. At first they opposed the inevitable changes by traditional means—ballots and bullets—but in the end, reversing thousands of years of history, they came to understand that it was their turn to flee. Thus the desperate and disaster-plagued "First Wave" of interstellar immigration from Earth had taken place: not courageous frontiersmen seeking new liberties and opportunities, as fiction writers had always imagined, but frightened authoritarians anxious to prolong their ancient and corrupt regimes. Excusing herself, Elsie looked in on Goldberry MacRame, who continued sleeping, all indications from the medical panel in her cabin in the figurative green. With nothing better to do until Grossfuss and her father finished discussing current events and began planning the subfoline's first experimental run (it had been delivered here by the shuttlecraft that brought them; their job was to test and "install" it) she wandered aft to examine what she could of the Victor Appleton's revolutionary superconducting power plant. Lights came on overhead as she melted through one bulkhead membrane after another, separating different compartments, and winked out behind her as she passed. Despite her curiosity about the new technology, her thoughts, almost despite her wishes, were still concerned with history. The technology with which the refugees had chosen to expedite their escape from Earth had proven as imperfect as their political philosophies, scattering the would-be escapees at random, not only in the depths of space, but—and more important—in the mists of time, as well. A decade later by any "objective" calendar, when the Solar Confederacy, with the aid of a technology that worked better, had started transforming itself into a Galactic Confederacy, launching a more successful "Second Wave" of immigration and exploration, its participants discovered human populations already long established among the stars. Their many civilizations had risen and fallen countless times, over an historical period that, for the people trapped in those rising and falling civilizations, had been as long, in some cases, as five thousand subjective years. Majesty was home to one such population, divided throughout its history into warring cultures that had burgeoned and collapsed in cycles. Warfare's senseless waste of lives and money and time had kept them primitive by comparison with the younger Confederacy. Like her father, Elsie wasn't certain what a "screwmaran" was, but she knew it would be handmade, capable, after a fashion, of navigating the Sea of Leaves armed with large versions of Goldberry MacRame's crude pistol (cannon, or perhaps flamethrowers), and powered by human suffering. Examining the subfoline's power-plant controls, Elsie shuddered at the thought. The emotional rejection of technology, she knew from her studies, at some arbitrary level of complexity—and comprehensibility, she suspected—between the bicycle and the combustion engine (or the bow and arrow, and the repeating rifle) was a feature common to many authoritarian pseudo-philosophies. Over the course of history, its ultimate consequences (intended or not) were always a drastic reduction in living standards, a shortening of individual life spans, the creation of an aristocratic elite, and the revival of slavery. Some of these dismal facts of Majestan history Elsie had absorbed without much thought during the voyage here. Like almost all Confederates, she possessed one of the cerebro-cortical implants her father had pioneered. It served her, as it served trillions of her co-sapients, as an alarm clock, calculator, computer, library, telephone, stereo, radio, and personal movie theater. No telltale lights glowed, for instance, on the medical machinery in Goldberry MacRame's cabin, any more than on the controls of the superconducting engines. Both communicated directly with her implant. The one thing it couldn't do, placed where it was when she was a baby, on the surface of her brain inside her skull, was light her cigarettes, which was all right with Elsie. She didn't smoke. And Confederate cigarettes lit themselves. Elsie dreaded the boredom and inactivity it would entail, but now she was grateful that the job her father had accepted would keep them below the surface of the Sea of Leaves, where no intelligent life ever ventured. (She decided to avoid thinking about the full implications of that statement until later.) It would be her task to study certain scientifically confusing phenomena reported there, while Howell and his monstrous mechanic tested the subfoline itself. "Herself", she corrected: the Victor Appleton, like all ships, was a "she". Elsie's own life was confusing enough at present, she reflected, without the extra complication of intra-Majestan politics. She was something of a scientific phenomenon herself, even in her own phenomenal civilization, having won the Scholarate of Praxeology her father had mentioned—her "Sc.Prax.", as she thought of it, a degree more difficult to obtain than any mere doctorate—from the University of Mexico's Von Mises College, at the age of fourteen. She was discovering, however, as young men and women had discovered to their dismay for thousands of years (as the sleeping Goldberry Mac- Rame had no doubt discovered in her own turn, perhaps no more than four or five years ago), that no amount of formal education ever quite prepared a person for a life outside of academia—or the many personal problems real life presents. Again Elsie considered the unconscious First-Waver. Tidied up, Goldberry MacRame had turned out, in the younger girl's envious estimation, quite beautiful, with lustrous honey-colored hair, and a soft, milky complexion touched, as a probable result of her profession—naval officer, hadn't Grossfuss claimed?—by the Majestan sun. For some reason she couldn't identify, this caused Elsie to think about the boy she'd seen earlier, the one with the lamviin. Although she didn't understand why, she became angry with herself. And struggled to control it. If this was what it meant to grow up—not knowing from one moment to the next what you were going to feel, or why—she didn't want any part of it. How was she going to tell her father what she'd done aboard Tom Sowell Maru? "Elsie?" Her thoughts were interrupted by the sound of her father's voice, and she heard his nails clicking on the deck before she saw him. She turned in the narrow companionway, away from the floor-to-ceiling panel she'd come here with the intention of examining. "Yes, Father, I'm here." He sat on his haunches and looked up at her. "Woolgathering? Well, I suppose there's no harm in it. As they say in Wyoming, "Fifty million coyotes can't be wrong". However, I did wish to consult with you in your paramedical capacity. If our young Antimacassarite guest's going to remain asleep for at least another couple of hours, Obregon and I thought we'd take the Victor Appleton out for a trial spin. What do you think?" Grinning, Elsie hunkered down beside Howell and put both arms around his neck. Despite her many accomplishments, she had no medical capacity beyond what she'd learned of first aid in the Galactic Girl Guerrillas, supplemented by some veterinary stuff she'd thought it a good idea to learn on her father's account. She was grinning for another reason, as well, having just discovered she looked forward to putting the subfoline through its paces a bit more than she'd realized. She readjusted her glasses and, folding her smart-suited legs beneath her, sat down on the deck. "The medical panel in the cabin says she's suffering from exhaustion, mild hunger, dehydration, maybe a touch of emotional trauma. I can understand that, if she lost her ship. The news service says both—maybe all three—sides lost the engagement up on the equator and a lot of people are dead or unaccounted for. I didn't want to try to sedate her, but I think she'll sleep." Howell's eyes crinkled in a manner Elsie knew represented an answering grin. She resolved then and there to confront him with the thing that had been troubling her. "Very well," he began, "Shall we be upon our—" "Before we do, Father, there's something—" "Mr. Nahuatl! The voice belonged to Grossfuss, coming from the bow of the subfoline, and it rang with panic. Holding her glasses to the bridge of her nose with a hand—the other resting on the handle of one of her pistols—Elsie hurried forward behind her father. When they got as far as the cabins, they saw Grossfuss standing at one end of the corridor. Between him and them, Goldberry MacRame leaned against the frame of the dilated cabin door membrane, swaying, her intravenous tube trailing from one wrist. In one hand she waved a gleaming scalpel she'd taken from the first-aid kit. "Mr. Nahuatl," Grossfuss complained from one corner of his mouth, the tone of his voice hinting that all this was somehow Howell's fault, "This is gettin' t'be a real bad habit with her." "Where have you hidden my sidearm, animal?" the girl demanded. "I shall see every one of you foul creatures broken and sent to the Steps! But first we must abandon this machine! It is about to be destroyed!"

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

|