L. Neil Smith’s THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE

Number 907, January 22, 2017

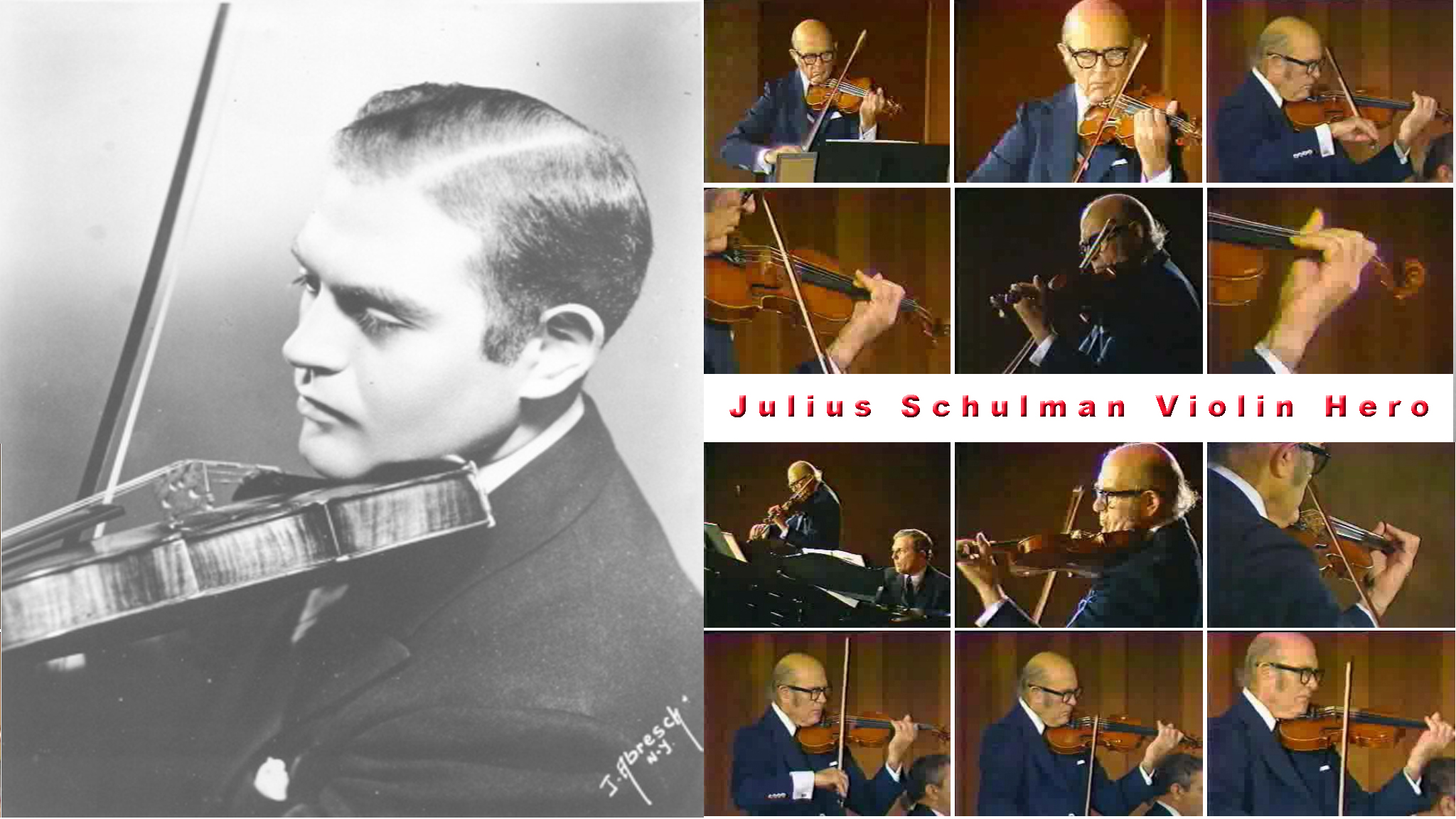

Julius Schulman Violin Hero

by J. Neil Schulman

[email protected]

Special to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

I became, first, a photographer, then a writer, then a filmmaker, because I did not learn to play the violin like my father, Julius Schulman.

My father, simply and demonstrably, was one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century, a century noted for master violinists such as Yehudi Menuhin, Efrem Zimbalist, Sr., Mischa Elman, David Oistrackh, Isaac Stern, Zino Francescatti, Leonid Kogan, and of course, Jascha Heifetz.

I grew up in a house where I could hear my father practicing the violin for hours every day.

I have a vivid memory of sitting enraptured at age four in front of a record player upstairs at my grandparents’ house in Forest Hills, New York, as my grandmother Sarah played for me radio broadcast transcriptions of my dad performing violin solos.

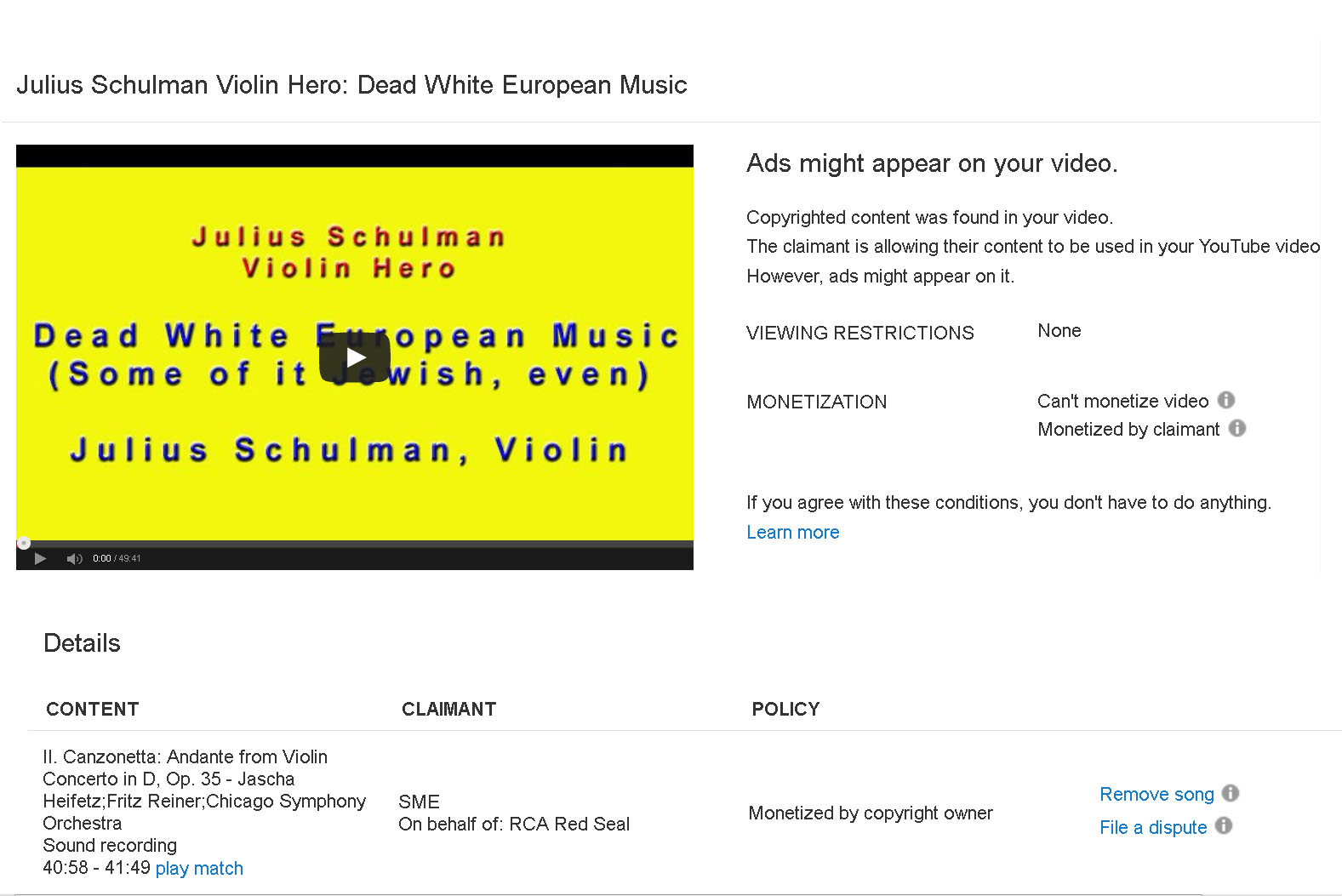

In the past few days I’ve had a “proof of concept” how good my father was on the violin. When I released one of my dad’s old radio recordings onto YouTube, I received a copyright infringement notice from RCA Red Seal records saying I had used a portion from one of Jascha Heifetz’s RCA records. Someone else might have been upset at the accusation of theft. I took it as one of the greatest compliments my father had ever received that my dad’s playing could be confused with Heifetz’s.

I’m told I sang the entire Mendelssohn violin concerto when I was four. Why I wasn’t started on violin lessons at that age is something I don’t know. I do know that when I did start violin lessons at age eight, with one of my father’s colleagues in the Boston Symphony as my teacher, I heard the sounds coming out of my violin—and compared it to what came out of the violin when my father played it—and quit practicing.

Whenever I was introduced to any of my parents’ friends I was always asked first thing whether I played the violin.

Consider that when Hercules murdered his children in a Hera-induced fit of madness Hera was probably doing them a favor. My father premiered his career at eight-years-old when he performed the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto at Carnegie Hall. In classical music this is called being a “prodigy.” In movies it’s called being a “child star”—and we know how many child stars have emotional problems when they grow up and are no longer treated as entitled. A grown-up child star often regards their own child as competition. Maybe that’s why my father wasn’t eager for me to be a violinist. Or maybe he was noble and just didn’t want his son to have to eat the shit that comes with being in such a ruthlessly competitive business. I sure showed my father, though. I became a novelist and filmmaker, totally secure professions in comparison to music. snort

So I grew up in hero-worship of my father and sixteen years after his death that has never gone away.

My father twice gave up chances to tour as a solo violinist with only expenses covered because it was the Great Depression and instead my dad accepted orchestra positions with a weekly paycheck, so he could send half his pay to his parents whose fortune had been wiped out in the Crash of ’29. My father bitched about that for the rest of his life but my mother, sister, and I wanted for nothing in a career in which my father got a steady paycheck for all but one year in an orchestra career stretching over a half century.

When in the 70’s I gave my father a copy of Harry Browne’s book How I Found Freedom in An Unfree World—which introduced him to the concept of “family slave”—my father said he wished he’d read that book before he made his career choices. I didn’t tell my dad that it would have created a time paradox because if he hadn’t made the choices he did I never would have been born so I couldn’t give it to him to read.

By the way, I got the idea for calling my dad’s YouTube music videos, play list, and YouTube channel “Julius Schulman Violin Hero” because “Jimi Hendrix Guitar Hero” is what rock music’s greatest guitar virtuoso was called.

Here’s some trivia regarding my dad:

- My father’s given name was Julian, not Julius, but his family called him Julie—as did most of his colleagues throughout his life. When his older sister Geri brought him to register for school she called him Julie—which the registrar wrote down as “Julius.” The name as registered for school stuck with him for the rest of his life.

- My father had no middle name.

- After my father passed my mom and I sold my dad’s Guarnerius violin, but I still have his first quarter-size violin that he learned to play on.

- My father went bald in his late twenties. He started wearing a toupee when the Mutual Network Symphony Orchestra began television broadcasts in the 50’s and the lighting crew complained that reflections off my dad’s bald head were flaring in the television camera. He quit wearing the toupee as a member of the Boston Symphony in the 60’s.

- His favorite author was Robert Ruark, who wrote novels about Africa. I had the pleasure of telling Nichelle Nichols—who got to name her Star Trek character “Uhura,” a femininization of the Swahili word for “freedom,” “uhuru”—because at the time she met with Gene Roddenberry regarding the role she was reading Ruark’s novel Uhuru—my father’s favorite.

- My father played in pit orchestras for Broadway shows, and his favorite musical was Meredith Wilson’s The Music Man.

- My father was a lifelong anti-Communist, which often caused him problems and certainly lost him jobs in a music industry rampantly populated by card-carrying Communists. But that didn’t stop my father from being close friends with fellow Boston Symphony violinist—and card-carrying Communist—Gerry Gelbloom, whom my dad picked to be my violin teacher. My father told me he distrusted Fidel Castro even before Castro came out as a Marxist-Leninist. My father told me, “I didn’t trust Castro because he smiled too much when there was nothing to smile about.”

- As a member of the San Antonio Symphony my father bought a bright orange Volkswagen camper for overnight trips with my mother, but he also used it to commute to work. The orchestra members immediately dubbed it “Orange Julius.”

My father’s influence on me didn’t end with music. When at age fourteen I borrowed his Nikon and Ricoh 35mm single-lens-reflex cameras (the lenses were swappable) to shoot a junior-high basketball game—which led to my regularly selling photography to local Massachusetts newspapers—I developed those photos in my dad’s basement darkroom.

My dad shot movies of his orchestra tours around the world with a Bolex 16mm movie camera—movies so professional they were played on TV and got my father an offer to become a union cinematographer for a Hollywood studio—and later in life, after my father’s death, I became a movie director.

My first lessons both in shooting guns and their usefulness in defense against criminals came from my father. My dad was an NRA member and every month I read in his subscription copy of American Rifleman the “Armed Citizen” column with newspaper clips detailing ordinary people using their guns to stop crimes.

My dad held a license to carry a concealed firearm in Massachusetts, New York City, Texas, and California. He defended himself with a handgun from gangs of muggers following late-night concerts in Boston and New York on five separate occasions, wounding no one and only having to pull the trigger once. On another occasion he saw a woman being carjacked on 72nd Street and used his handgun to order the carjackers out of her car. The would-be victim sped off safely.

My dad applied for a license to carry a concealed handgun as a member of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, when after a late-night concert a fellow violinist in the orchestra was mugged, beaten up, hospitalized, and his violin smashed. My father played in orchestra concerts a Guarnerius violin dating back to 1716—an irreplaceable antique. This was not going to happen to him.

My dad made his license application at our local police station in Natick, where we lived. The Natick police captain licensing my dad told him the story that one of the first times my dad deposited his symphony paycheck at a local Natick bank the silent alarm was set off. My father had opened his violin case (which he also used as a briefcase) to take out the check. The clerk who set off the alarm had thought my father was about to pull out a machine gun from the violin case.

At the time my father was given a license to carry a concealed handgun in New York City—1970 to 1975—only ex-cops, family of cops, private security agents, and private detectives were given carry licenses, although exceptions were sometimes made to wealthy applicants who slipped the desk sergeant $5000 and a bottle of Chivas Regal scotch. My dad didn’t have to pay the $5000—only the bottle of scotch—because as a concertmaster for the Metropolitan Opera he was considered New York royalty. But my father nonetheless took his responsibilities as a gun-carrier seriously and practiced regularly at the firing range where—he told me—most of the security guards, private detectives, and cops looking for extra practice “couldn’t hit anything.”

Later in life I wrote Op-Ed articles about gun defenses on the editorial pages of the Los Angeles Times and Orange County Register, and in National Review. These articles and much more were collected in my 1994 book Stopping Power: Why 70 Million Americans Own Guns, and my dad got to see the front book cover with this praise from Oscar-winner and NRA President, Charlton Heston: “Mr. Schulman’s book is the most cogent explanation of the gun issue I have yet read. He presents the assault on the Second Amendment in frighteningly clear terms. Even the extremists who would ban firearms will learn from his lucid prose.”

The truth be told in full, my fascination with the violin and classical music has influenced my entire professional career as a writer and filmmaker.

My first novel, Alongside Night, contains in the quotations on the novel’s frontispiece, “Tzigane—Maurice Ravel.” That gypsy-style violin piece played by my dad —“tzigane” being the French word for “gypsy”—was on my mind while writing about gypsy cabs, the counter-economic transportation Elliot Vreeland uses during a collapsing New York City’s unending transit strike. In the movie adaptation of Alongside Night the Ravel Tzigane became the musical theme of the movie’s underscore.

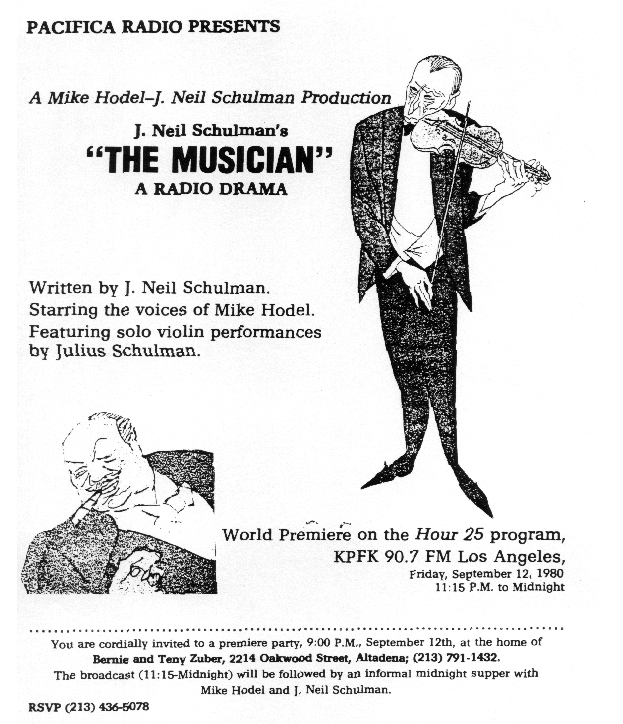

In 1980 my short story about a violinist “The Musician”—in 1981 published in the magazine Fantasy Book—was broadcast as a radio play.

My second novel published in 1983, The Rainbow Cadenza, took all my musical knowledge to adapt the idea of contemporary planetarium-based Laserium shows into a futuristic fully-realized visual music. I wrote most of the novel in 1981 while staying with my parents in San Antonio, so I could pick my dad’s brain as necessary.

After the sale of my script “Profile in Silver” to CBS’s Twilight Zone broke me into screenwriting, my first feature-length screenplay was No Strings Attached, about a violinist who must learn to play again after suffering a hand injury. That script was published in my 1999 book Profile in Silver and Other Screenwritings, for sale on Amazon.

In the first feature film I wrote, produced, and directed, Lady Magdalene’s, one of the characters is a violinist. Despite the character being the bad guy the movie is dedicated to my dad. All violin playing you hear on the Lady Magdalene’s movie soundtrack is by my dad.

So here’s to my father, Julius, my violin hero.

His official web page, Julius Schulman: Life With A Violin.

His Official YouTube Channel, Julius Schulman Violin Hero.

Oh, and here’s my mom talking about her life with my dad, an interview I did with her on Mother’s Day, 2007.

Reprinted from

J. Neil Schulman @ Agorist.com

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

Just click the red box (it's a button!) to pay the author

![]()

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy found here. (Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)

TLE AFFILIATE

![]()