On Liberty, by John Stuart Mill

Reviewed by Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Special to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

During the libertarian rebirth of the past generation, it has become fashionable to sneer at the essay On Liberty. It is, I admit, a flawed work, and I will shortly try to explain why this is so. Before then, however, I will put a case for the defence—to show why, despite its flaws, the essay remains a valuable weapon in the libertarian arsenal, and will remain one when Rand and Nozick will chiefly be names found in histories of twentieth century thought.

Mill is at his very best in Chapter II, “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion”. This contains the best argument for freedom of speech that I have ever found. Briefly stated, it goes thus:

We have no means of knowing with complete certainty the

truth or falsity of any proposition. Therefore, to prohibit its being

advanced is to make a wholly unfounded assumption of infallibility. Moreover,

if a prohibition is made, one of two consequences will follow:

First, if the proposition is true, humanity will lose whatever

benefit might follow from an addition to the stock of existing truths;

Second, if it is false, we shall lose what little assurance we

can have of the truth of the other proposition denied by it. Establish even

the plainest truth by law, and it will dwindle from the status of a truth

acknowledged by reason to the status of a prejudice that can be embarrassed

by the feeblest opposing show of reason.

When putting this argument, I have sometimes been called a racist, and was once pelted with beer glasses. But I have yet to hear or read a reply to it that I feel worth considering.

Mill also says much of permanent value in his discussion of what we call “health activism” and “the War on Drugs”. Take this against the drug controllers:

[N]either one person, nor any number of persons, is warranted in saying to another human creature of ripe years, that he shall not do with his life for his own benefit what he chooses to do with it. He is the person most interested in his own well-being,…. All errors which he is likely to commit against advice and warning, are far outweighed by the evil of allowing others to constrain him to what they deem his good. (chapter iv)

Again, take this against Mr Steve Woodward of Action on Smoking and Health and all the other salaried enemies of free choice:

To tax stimulants for the sole purpose of making them more difficult to be obtained, is a measure differing only in degree from their entire prohibition; and would be justifiable only if that were justifiable. Every increase of cost is a prohibition, to those whose means do not come up to the augmented price; and to those who do, it is a penalty laid on them for gratifying a particular taste. Their choice of pleasures, and their mode of expending their income, after satisfying their legal and moral obligations to the State and to individuals, are their own concern, and must rest with their own judgment. (Chapter v)

There is much else that I can say in favour of this essay. There is its compactness, its rhapsodic praise of individuality, its biting denunciation of bigotry and paternalism. There is its honesty, and its willingness to give full and fair consideration to all opposing points of view. There is its brevity: it can be read and considered in less than a singly evening. But I will turn now to its defects, of which I see two.

In the first place, Mill fails to identify what has turned out to be the real threat to freedom. He says much in his opening chapter about “the tyranny of the majority”. He claims that this works through the administrative organs of a democratic state, and through the unaided pressure of public opinion. In both areas, he is wrong.

There is, I admit, a certain pressure exerted by one’s neighbours to conform to whatever is the currently accepted behaviour. But anyone who looks at a civilised country in 1859, when this essay was first published, and the same country today, will see a great diminution in the power of public opinion over the individual. The growth of cities has at once provided anonymity for many disapproved acts, and refuge for their perpetrators in communities of like-minded individuals. Equally, there has been an immense growth of private toleration. A person today can safely do many things that in the 1850s would have led to his being shunned. There are few things for which he will now be shunned that were entirely respectable in 1859.

Of course, it is something else if we look from public opinion to the criminal law. Here, there has been a decided loss of freedom. Yet, though every restriction has been made in the name of the majority, it has seldom been made at the urging of the majority. In at least this country, majorities have been at fault less for an eagerness to restrain than for their utter indifference to any question that does not obviously and immediately affect them. Take, for example, a question that has been controversial from Mill’s day to our own—the legal status of homosexual acts. There was no majority in 1861 for removing buggery from the list of capital offences; and there was none in 1885 for creating the new offence of gross indecency between males; and none in the 1940s and 50s for strictly enforcing that law, and none in 1967 and 1994 for liberalising it. Nor will there be a majority in favour when the next Labour Government not only removes the remaining disabilities, but replaces them with privileges. In this question, as in most others, laws have for good or ill been made at the prompting of well-organised pressure groups representing no one but their own members—but skilled in claiming democratic endorsement.

Quite often, indeed, these pressure groups have obtained laws, the principle behind which if ever explicitly followed would be fatal to democracy. I think of compulsory state education. The principle behind this is—that most parents are too stupid to see the value of education for their children; and that, even if they do value education, they are unable to decide what kind is best. Now, plainly, if people cannot be trusted to choose properly in a matter that so closely affects them, I do not see what argument there can be for letting them elect a government.

And this brings us to the irony of Mill’s position. Since 1859, by far the most active and successful of these despotic pressure groups have been the very middle class elites that Mill thought a necessary barrier between the majority and its destruction of all that is noble and good, and that he wanted in his essay on Representative Government to strengthen with double votes and separate representation.

Certainly, Mill was right to fear majority government. It is not a harmless—still less a benign—institution. The questions that majorities think important often do require or allow limitations of freedom—the welfare state, together with the taxes and prohibitions on which it rests, is a prime instance. But by far the worst effect has been the confusion of who rules and who is ruled. Majority government has enabled the authoritarians to shield themselves behind the “notion, that the people have no need to limit their power over themselves.” (Chap i) This has led to a dangerous erosion of constitutional restraints in the United States, and to their nearly complete atrophy in our own country. As a recent illustration of this tendency, take the War Crimes Act 1993. The Act is retrospective. Even so, it will remain useless until such time as its promoters secure a further dispensing with the rules of common law. This was twice argued by the Judges in the House of Lords. Their arguments were denounced as opposition to the will of the people. Yet, in plain fact, the law expresses this will in hardly any but the formal sense. We might almost as easily call the laws of Augustus and his successors expressions of the popular will because they usually contain some reference to the authority of the Senate and Roman People.

In the second place, Mill fails to explain what he means by freedom. In his first chapter, he begins a definition with a great flourish:

The object of this Essay is to assert one very simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual in the way of compulsion and control, whether the means used be physical force in the form of legal penalties, or the moral coercion of public opinion.

Speaking for myself, I want a society in which the greatest number of individuals have the greatest permanent chance of avoiding whatever makes them unhappy. I will leave out most steps in the subsequent argument; but if anyone proposes a restraint on individual choice, I ask two questions:

First, will the principle derivable from the proposed restraint be one that, applied in all relevant cases, advances or hinders progress towards the society that I want?

Second, are there any particular circumstances that make it the lesser of two evils to set aside the answer to the above question, and accept or reject the proposed restraint?

Now, this is not “one very simple principle”. It explicitly requires an understanding of law, economics, sociology, history, and every other branch of moral philosophy before any prescriptions can confidently be made—and then they can only ever be provisional. I have enjoyed what by most standards has been an unusually long and elaborate education; and it has left me acutely aware of how little understanding I have in these areas. To replace all this with “one very simple principle” would save me a lot of hard thinking and greatly simplify the case for freedom.

So what is this “one very simple principle”? It is

that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. (Ibid)

And here we have it. I must confess that when I first read these words as a boy of 17, I was converted on the spot. They seemed to express everything that I was groping toward. Soon, however, the obvious difficulties crowded in, to leave me a convinced but momentarily perplexed libertarian.

What is meant here by “harm”? If my readers grow bored with this review, and put it down unfinished, they are harming me. Many devout Moslems were undeniably harmed by the publication of The Satanic Verses. Those people who boycotted Barclay’s Bank so long as it did business in South Africa were harming the shareholders. Anyone who introduces a new piece of machinery into his business, and thereby reduces his need for labour, is harming some of his employees. Moreover, if all these acts are harmful, is it not “self-protection” to do something about them?

The usual answer to this objection is to limit the meaning of “harm” to certain classes of act. Mill does try this. In Chapter iv, he allows restraint where “a distinct and assignable obligation to any other person or persons” is violated. A few paragraphs later, he exempts from restraint “conduct which neither violates any specific duty to the public, nor occasions perceptible hurt to any assignable individual except himself”. There are further indications throughout the essay that Mill means by “harm” exactly what we all mean; and that he would have had no time for the bigots and social controllers who twist his use of the word to the remotest meanings.

The problem, however, is that the “one very simple principle” does not itself contain these limitations. In its normally accepted meaning, the word “harm” can describe the acts that I mention above. If limitations are to be made, they must be derived from other principles which stand alone and which might supersede his “one very simple principle”.

In fact, after much effort to make his principle generate the applications for which it is clearly intended—and no more—Mill does quietly give up:

In many cases, an individual, in pursuing a legitimate object, necessarily and therefore legitimately causes pain or loss to others, or intercepts a good which they had a reasonable hope of obtaining. Such oppositions of interest between individuals often arise from bad social institutions, but are unavoidable while those institutions last; and some would be unavoidable under any institutions. Whoever succeeds in an overcrowded profession, or in a competitive examination; whoever is preferred to another in any contest for an object which both desire, reaps benefit from the loss of others, from their wasted exertion and their disappointment. But it is, by common admission, better for the general interest of mankind, that persons should pursue their objects undeterred by this sort of consequences. In other words, society admits no right, either legal or moral, in the disappointed competitors, to immunity from this kind of suffering; and feels called on to interfere, only when means of success have been employed which it is contrary to the general interest to permit—namely, fraud or treachery, and force. (Chap v)

This says more or less what I say above, but uses the more nebulous criterion of the public interest, and is only implicit in its rule-utilitarianism. But, clearly, once Mill states this principle, the one that it is his stated purpose to assert becomes wholly redundant. It is from this latest principle that all the wisdom in his essay derives, not from any nice definitions of “harm”.

It is easy to laugh at this failure. But has anyone found a better simple principle? I have been told “Thou shalt not commit aggression”, and that freedom is the absence of force. I have read much about “consent” and “the equal rights of others”. These all contain the truth. But they all break down as self- contained definitions of the truth. Therefore, unless we start talking about natural rights—and how far these will get anyone I will not now provoke my readers by saying—we are left with something like the approach that I describe above, and that Mill finally concedes. It is long-winded, but has the advantage of describing how most libertarians actually think. It explains the agonising over foreign policy and immigration control that according to the orthodox definitions of freedom ought not to happen.

This completes my review of what Mill wrote. I will pass now to how well he has here been published. Sadly, there is much to be criticised. In the first place, the scanning of the printed text was imperfectly done. In several places, the scanner read lower case text as upper case. Nowhere does this cause ambiguity, but it is always a nuisance—especially since the WordPerfect spell checker is able to detect and remedy it.

Again, in Chapter iv of my printed edition, there is the Greek word pleonexia. This is replaced in the electronic edition by the ellipsis “[greekword]”. Although Greek characters cannot go into simple ascii text, there is no reason why they cannot be given a direct Roman transliteration, even if stripped of their accents. By itself, a single omission in the present essay is unimportant. But we are at the beginning of a mass transfer of literature from one medium to another—much of which literature will have quotations in Greek and other languages which use non-ascii characters. It is therefore important for proper scholarly conventions to be established from the start.

Finally, the printed edition used was an American one. I have no principled objection to Websterised spellings—they may, after all, become standard English spellings during the next century. Nevertheless, when scanning a text, it strikes me as plain good manners to give those who will be using it as original a version as possible.

And this does complete my review. Despite a few reservations, I welcome the present electronic publication. I look forward to the electronic publication of Mill’s more substantial works. His System of Logic comes to mind. Have any of my readers a good scanner and time on their hands?

Editor’s Note: This essay was first published many years ago and electronic editions now are much more common. Many of Mill’s books can be found at Project Gutenberg. Go to that link and search for Mill, John Stuart on the "M" page.

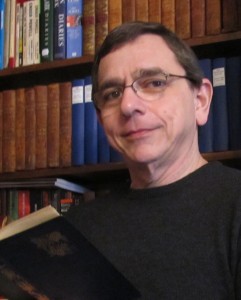

Sean Gabb is the author of more than forty books and around a thousand essays and newspaper articles. He also appears on radio and television, and is a notable speaker at conferences and literary festivals in Britain, America, Europe and Asia. Under the name Richard Blake, he has written eight historical novels for Hodder & Stoughton. These have been translated into Spanish, Italian, Greek, Slovak, Hungarian, Chinese and Indonesian. They have been praised by both The Daily Telegraph and The Morning Star. He has produced three further historical novels for Endeavour Press, and has written two horror novels for Caffeine Nights. Under his own name, he has written four novels. His other books are mainly about culture and politics. He also teaches, mostly at university level, though sometimes in schools and sixth form colleges. His first degree was in History. His PhD is in English History. From 2006 to 2017 he was Director of the Libertarian Alliance. He is currently an Honorary Vice-President of the Ludwig von Mises Centre UK, and is Director of the School of Ancient Studies. He lives in Kent with his wife and daughter.

Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Tel: 07956 472 199

Skype: seangabb

Postal Address: Suite 35, 2 Lansdowne Row, London W1J 6HL, England

The Liberty Conservative Blog

Sean Gabb Website

The Libertarian Alliance Website

The Libertarian Alliance Blog

Richard Blake (Historical Novelist)

Books by Sean Gabb

Sean Gabb on FaceBook

and on Twitter

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

![]()

AFFILIATE/ADVERTISEMENT

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy

found here. (Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)