They Took Away the Doughboy’s Rifle

by Vin Suprynowicz

[email protected]

Special to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

(Note: This report was originally posted at the Web site of “Firearms News,” https://www.firearmsnews.com/editorial/the-u-s-postal-service-took-away-the-doughboys-rifle/359421. Please patronize their advertisers.)

We’ve all heard stories about young children being punished at school by their socialist teachers for drawing or cutting out pretend handguns, or even for pointing a finger on the playground and saying “Bang! Bang!”

And some of us did sound the alarm about the “slippery slope,” years ago, when the forces of Political Correctness realized how easy it was to start rewriting history by “digitally editing” old historical photos. After all, why NOT remove the cigarette holder from old photos of President Franklin Roosevelt? You don’t want today’s kids to think it’s OK to smoke, do you?

But surely we’ll never reach the point where gun haters in a U.S. government agency will actually start doctoring images to remove the rifles (the arms with which Americans won and have long defended our freedoms) from the hands of American COMBAT SOLDIERS, will we? — altering an image of a soldier in combat, removing the piece of equipment on which his survival depended, to make it appear that U.S. soldiers CARRY NO NASTY RIFLES when they go to war?

They’ll never go THAT far. Right?

In fact, it’s already happened.

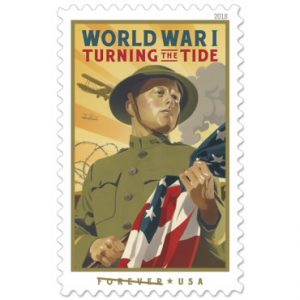

Standing in line at the post office the other day, I noticed a poster on display showing eight newly issued commemorative stamps, along with a sheet of 20, behind glass, of one of the new stamps, called “World War I / Turning the Tide.” In the background of this stamp can be seen a biplane, a shell burst, and some barbed wire. In the foreground, a uniformed and helmeted U.S. doughboy strides bravely ahead, holding close to his chest an American flag.

I have nothing against featuring the American flag on a stamp, mind you. But look at the way that soldier’s arms and hands are positioned. You’ve seen men on combat patrol holding their arms and hands in that position plenty of times. But they weren’t holding flags.

In the revolutionary war and even as late as our Civil War, specially designated American soldiers did march into battle carrying flags, sometimes on flagstaffs called “spontoons”—essentially half-pikes with pointed steel lance-heads on the business ends, which could be used as weapons of last resort.

In an era when standard tactics called for masses of men, standing upright in closed ranks, to blast the enemy with volleys of otherwise highly inaccurate musket fire, this made sense. In the dust and black-powder smoke of battle, the flags helped both commanders and men keep track of their units and their movements.

But by 1917, by which time the easy-to-target brightly colored uniforms of 1914 had been quickly replaced with clothing better suited to blend into the blasted environment of No-Man’s-Land, essentially NO ONE still marched toward enemy machine guns carrying brightly colored flags—certainly not encumbering their arms, where their rifles should have been.

The image on the stamp makes no sense.

It was obvious, even at a quick glance, what had happened: This design, this composition, had been altered. The soldier’s hands were originally positioned that way to hold not a flag, but a rifle.

I emailed artist Mark Stutzman in Maryland, who designed the “Turning the Tide” commemorative and who had earlier drawn the Post office’s popular 1993 “Elvis” and “Buddy Holly” stamps. In his original design, as submitted, had the American doughboy held a rifle in his hands?

A LITTLE ‘GUN SHY’

He replied: “Hi Vin, Thanks for writing. Interesting that you should bring this up. My original proposal was with a rifle.”

A source familiar with the back-and-forth between artist Stutzman and the Postal Service told me the USPS “Stamp Advisory Committee” was “a little ‘gun shy’ about the rifle being so prominent.” Stutzman declined to confirm that for the record.

“We debated a few options and settled on him holding the flag instead,” Stutzman told me. “It seemed to bring some patriotism forward and helped identify him as American more immediately. Since stamp images are so small, there’s a need for immediate comprehension. In this case the read of hierarchy is WWI soldier, America, and war (barbed wire, plane, smoke). . . . I am somewhat speculating on the reasoning for why the decision (to remove the rifle) was made since I got information about committee meetings second-hand through the art director. He may be a better source for info and also have a direct line with the Postal Service. Greg Breeding is his name. … Super guy and easy to talk to.”

Not so much. After several days of ducking my emails and phone messages, art director Breeding, in Charlottesville, Virginia, finally sent me his polite refusal to talk:

“Hello Vin, Thank you for your interest in the World War I stamp. It was my deep privilege to art director this issuance to commemorate America’s role in bringing World War I to an end. Such an incredible part of our history.

“Regarding your questions, it is the policy of the Postal Service to direct these types of inquiries to Public Relations.…”

Said PR guy “will be happy to assist you and, sometimes, he will subsequently involve the art directors and other Postal employees as well.”

Not so much.

Although I called during business hours, I ended up leaving a voicemail message with the Postal Service Public Relations office in Washington. No one there would actually talk to me by phone, or let me talk to anyone directly involved in the decision to remove the rifle. Public Relations guy Carl Walton did send me a brief email, asking the nature of my inquiry.

I emailed him that Mark Stutzman had confirmed his original design included the rifle, but that he “was reluctant to be quoted about the thinking process of the advisory committee, explaining he only heard about their suggestions/requests second-hand.…

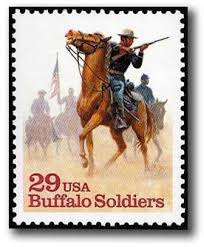

“I find it interesting that there’s apparently now some reluctance to show a U.S. soldier carrying a rifle, even as he walks into combat (barbed wire & shell burst behind),” I continued. “As recently as 1984, the ‘Buffalo Soldier’ stamp showed a cavalryman SHOOTING his rifle. I’m looking for some background on who makes up that advisory committee, how they got there, and their thinking about eliminating the rifle. A direct quote from someone involved in the process, explaining their thinking, would be great. I’d be happy to talk with such a person on the phone.

“I’m also hoping we can get an image showing Mark Stutzman’s initial proposed ‘vertical’ version of the stamp, with the rifle — as a JPEG, a color photocopy, or whatever.”

I asked for the names, states of residence, and (brief summary) qualifications of those who sit on the advisory committee. Also, “I wonder if you can tell me whether any of them is a veteran of the armed forces, and/or a gun owner? (Only about 7 percent of Americans are now veterans, but Gallup reports 47 percent of American households own firearms.) Thanks again for your help.”

In the end, Carl Walton, who’s paid about $57,000 a year (plus benefits and pension), presumably to find the answers to reporters’ questions, refused to let me talk to anyone who actually took part in the decision to remove the rifle. Instead, he e-mailed me a cobbled-together piece of bureaucratic double-speak which answered virtually none of my questions:

“Dear Mr. Suprynowicz, Thank you for your inquiry about the United States Postal Service’s 2018 World War I stamp. In designing this stamp, the Postal Service wanted to express the many ways in which the United States contributed to turning the tide of the war.

“The design team drew inspiration from the illustration, typography and poster work of the World War I era. Many concepts were evaluated and discussed as the design team considered which aspect of the history of WWI to focus on. Early sketches may have included a soldier holding a rifle, but when we reviewed color studies, the designs were flat and brown. To work as a stamp, the artwork needed a strong colorful focus, something to grab the viewer.

“The designers realized that with all of the detail in the initial sketches, it wasn’t immediately clear that we were honoring the American contribution to World War I. As we were already working in a poster-like style, we decided to focus on a single image that would be a patriotic representation of the American presence in the war and not a literal scene. The inclusion of the flag gave this stamp much needed color and a strong, patriotic message.

“This design direction was presented to the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee and is the one they endorsed and sent forward to the Postmaster General for consideration.

“We believe this stamp is a beautiful and proud symbol of the American spirit. Thank you.”

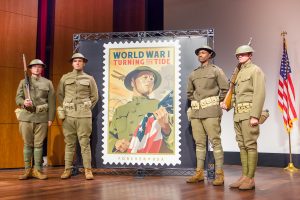

(above: unveiling of the stamp at the World War One Museum, Kansas

City)

AND GUN-FREE, OF COURSE

Personally, I always thought the 1903 Springfield and the 1917 Enfield were “proud symbols of the American spirit.” But public-relations guy Walton says “Early sketches may have included a soldier holding a rifle”?

Artists don’t generally get awarded contracts to design postage stamps based on “rough sketches.” The main element of Stutzman’s design—as is obvious to anyone looking at the finished stamp — was a soldier holding a rifle. Why is the rifle gone?

Few of the greatest and most collectible U.S. postage stamps look like a Day-Glo kid’s toy box. And the point isn’t whether they wanted to add a flag — a brightly colored flag could have gone over the doughboy’s shoulder, in the background. The question is why they used it to REPLACE THE RIFLE.

(I asked again if they’d send us a copy of the original version with the rifle, so we could display a “before-and-after,” showing how “flat and brown” the stamp looked. The Postal Service refused.)

What were Carl Walton’s “many (other) ways in which the United States contributed to turning the tide of the war?” Did our soldiers and Marines accomplish that by operating soup kitchens or handing out propaganda pamphlets? No—and no such activities are featured on the stamp.

Yes, we sent war materiel—in fact, it’s now the general consensus that the passenger liner Lusitania—the sinking of which helped lead Woodrow Wilson to take us to war (mere months after he won re-election with the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War”)—was carrying ammunition and other contraband war supplies from the States, in violation of America’s supposed neutrality, when she went down. But there are no images of stevedores loading merchant ships on the stamp.

The airplane in the background? Yes, some brave Americans flew with French and British squadrons. But they didn’t “turn the tide.” In fact, few if any of the promised American-built planes or their aluminum V-12 “Liberty” engines ever made it into combat. Even the celebrated Browning Automatic Rifles never made it off the docks in New York during the 19 months America was in the war.

No, there’s only one way American troops helped to “Turn the Tide” in the First World War:

In March, 1918, after Russia dropped out of the war, the Germans launched a final, massive attack along the Western Front, hoping the influx of 50 divisions from the East would overwhelm the Allied forces in France before millions of Americans could cross the Atlantic.

The Germans captured the Belleau Wood, adjoining the Metz-to-Paris highway, barely 50 miles northeast of Paris

By June 4, more than 2,000 Germans with at least 30 machine guns were dug in.

In the first few days of June, the U.S. 4th Marine Brigade dug in just to the southwest of a wheat field that separated them from Belleau Wood. The battalions in the 5th Marine Regiment established themselves on the left, and those in the 6th Marine Regiment on the right.

When the Marines were told to clear the Germans from the Belleau Wood, they didn’t reply, “Gosh, you mean, charge right into their machine guns and everything? I don’t think so, sir. I think we need a ‘time out’ and an emotional support puppy.”

On June 6, without artillery support, United States Marines charged across 800 yards (a half-mile) of open wheat fields into German machine-gun fire—and into the woods. The adversaries clashed in bitter hand-to-hand fighting with knives, rifle butts, bayonets, and trench shovels. As Marine officers and NCOs fell dead or wounded, junior officers and enlisted men took their places.

First Sergeant Dan Daly, a recipient of two Medals of Honor who’d served in the Philippines, Santo Domingo, Haiti, Peking and Vera Cruz, famously shouted to his men of the 73rd Machine Gun Company “Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?!”

Repelling a German counter-attack, then-Gunnery Sergeant Ernest A. Janson—serving under the name Charles Hoffman — repelled an advance of 12 German soldiers, killing two with his bayonet (attached to his RIFLE) before the others fled. He became the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor in World War One.

In the end it took three weeks, but the Marines took back the Wood. The 4th, 5th and 6th Marine Brigades were awarded the French Croix de Guerre. Of its complement of 9,500 men, the Fourth Brigade suffered 1,000 killed in action, with 4,000 wounded, gassed, or missing—a 55 percent casualty rate.

They did not go after the Germans with soup kettles or propaganda brochures. Clearing Belleau Wood wasn’t cheap—9,000 casualties overall; 1,800 American dead. But when it was over, the Germans were stunned. They found their new enemy so fearsome they dubbed them the “Devil Dogs,” the “Hounds from Hell.” Two things shocked the Germans: One, the fact that the Marines never stopped, even when every commissioned officer in a unit was killed or wounded, they just kept coming. And the second thing that stunned them was the Americans’ MARKSMANSHIP. An official German report classified the Marines as “vigorous, self-confident, and remarkable marksmen.”

European conscripts tended to point their weapons in the general direction of the enemy, close their eyes, and jerk the trigger. Not these Americans.

Black Jack Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, summarized what the Americans had proved: “The deadliest weapon in the world is a United States Marine and his rifle”

Not his soup ladle. Not his propaganda brochure. His rifle.

I CALL THE CHAIRWOMAN OF THE COMMITTEE

One thing in Public Relations guy Walton’s little essay did intrigue me. He wrote: “The inclusion of the flag gave this stamp much needed color and a strong, patriotic message. This design direction was presented to the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee and is the one they endorsed.”

So: Did someone at the Postal Service actually remove the rifle BEFORE the citizens advisory committee saw the design?

Walton, of course, had refused to give me the names or personal contact information for any of the 12 members of the advisory committee, let alone tell me if any are Armed Forces veterans or gun owners, who might have been expected to raise a fuss about erasing the rifle. (And if there are no veterans or gun owners out of 12, so much for this “diversity” we’re always hearing about.)

But I’ll let you in on a little secret. As a highly trained investigative reporter, I belong to a very select group who are in possession of a certain high-tech, Buck-Rogers-type piece of investigative equipment far beyond even the imaginings of many an average American of only a few years ago. It’s called a “personal computer,” connected to a highly secret microwave network called the “Internet.”

In about 60 seconds I was able to come up with the committee members’ information on my own, including the fact that the chairwoman of the advisory committee is 68-year-old Janet R. Klug of Pleasant Plain, Ohio, past president of the American Philatelic Society and author of “Guide to Stamp Collecting” (2008) and “100 Greatest American Stamps” (2007)—on the cover of which is displayed the 1847 five-cent Franklin, which is—sorry—dull and brown.

Mrs. Klug, who was appointed to that position in 2010, is a registered Democrat. (In fact, it appears she’s the only Democrat living on a road with 13 Republican households.) In about another 30 seconds, I was also able to come up with her phone number.

So a little before Lunchtime, Ohio time, Friday April 5, I called, politely introduced myself, and asked Miss Klug if the rifle had already been removed from the design when the “Turning the Tide” stamp was forwarded to her committee.

“We don’t talk about our work,” she said, sounding pretty agitated.

“So your work on these stamps is a secret process?”

“It’s not a secret process!” she said, pretty emotionally. “It is the way we work! I’m not going to talk to you any more; Goodbye.”

And she hung up on me.

It seems like the folks who removed the rifle from that stamp really don’t want to explain themselves.

THEY TOOK AWAY HIS GUN

Where is this Political Correct move to strip the guns from our history going to end? Will our grandchildren be taught in school that General Gage sent his Redcoats to Lexington and Concord in April of 1775 to take away not their muskets, cannon, powder and ball, but rather the Patriots’ soup kettles and propaganda pamphlets?

This ongoing purging of our history—tearing down statues of the Founding Fathers (even the ones who called for an end to slavery and freed their slaves—hardly a popular or even an easy act at the time) and quietly purging all traces of the firearms that won our freedom—isn’t conducive to a reasoned, evidence-based discussion of the millions of civilians murdered by their own governments in Stalin’s Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany and Mao’s China and Pol Pot’s Cambodia—all Socialist tyrannies—because they had no firearms with which to defend themselves.

No, no. The hoplophobes hope we won’t notice what they’re up to—Michael Bellesiles writing his fraudulent book “Arming America” about how his fake study of Last Wills and Testaments supposedly proved Americans of previous generations didn’t generally own guns (but when skeptics asked to see his raw data, including from San Francisco before the fire, it was, um … “lost in a flood”), and now the newer sequel, the bogus claim that America has “more mass shootings” than any other country — conveniently ignoring the higher rates of shooting-deaths-per-capita in Norway, Serbia, and France, not to mention blood-soaked Mexico, Eastern Europe, and half of Africa.

(See: https://www.twincities.com/2018/11/26/john-lott-gun-free-zones-invite-mass-shootings/ .)

They hope we won’t notice their literally taking the rifles out of the hands of the American heroes of yesteryear—and that if we DO notice, they can put us off with a bunch of cleverly worded double-talk about “preliminary sketches” and “the many other ways” (other than troops shooting rifles) “that Americans helped turn the tide” … and finally about how guns are just so dull and brown and dirty looking.

But we’ve noticed. We’ve noticed that the stonewalling sneering bureaucrats and growling left-wing harridans of the United States Postal Service have taken this particular doughboy, who was willing to march to death or glory for his country in a war he never asked for—a doughboy now long in his grave, his voice of protest stilled—and stripped his rifle from his arms.

p.s.—By the way, one of the other eight new stamps on that poster in the post office? It honors America’s “first responders.” There’s a fireman, an ambulance attendant/technician, and a police officer. The police officer, responding first to the scene of a crime? In his only visible hand he holds … a flashlight.

– V.S.

Reprinted from https://www.vinsuprynowicz.com/?p=7494

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

![]()

AFFILIATE/ADVERTISEMENT

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy

found here. (Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)