A Story for Our Times

by Sean Gabb

[email protected]

Special to L. Neil Smith’s The Libertarian Enterprise

I remain sceptical about the direct impact of the Coronavirus. When I say sceptical, I don't mean that I deny outright there is any danger, but that I shall need to see much higher rates of infection and death than we so far have before I start taking serious precautions.

This being said, I am struck by the secondary effects of the virus on just-in-time and globalised supply chains. There are sound reasons for free trade and for generally turning the world into a single marketplace. This has done much to keep the peace and to enable our present wealth. The disadvantage is that the resulting structures of supply and distribution are more sensitive than they used to be. Everyday essentials must be brought in from far away, and there are limited stocks at any one time. There is a continual risk of disruption. We can see this at the moment in empty supermarket shelves. We may soon have to live as best we can with chronic shortages of basic foods.

This brings me to the advertising element of my posting. During the past few years, I have found that I am not much worse at marketing my books than mainstream publishers. These are organisations stuffed with English graduates whose idea of selling is to have lunch with old university friends who work for the larger bookshops. They are useless at direct selling. They are incapable of correcting typos after publication, or of changing Amazon product descriptions to reflect passing events. Posters at railway stations are almost invisible to a public hardened to omnipresent advertising. Newspaper reviews have no measurable effect on sales. Unless already famous, no writer who does business with them has any chance of growing rich. I was lucky to do well out of the old system, before it was overwhelmed by the new technology. This was a stroke of luck that I do not think will be repeated.

With this in mind, I have, where possible, been wheedling back the rights of my early books from the mainstream publishers. As said, I am not much worse at marketing, and am usually better; and the royalties are so much higher that I do better even with fewer sales. In particular, my Greek and Latin books address too small a niche to be of commercial interest, but bring me several hundred pounds a month via Amazon.

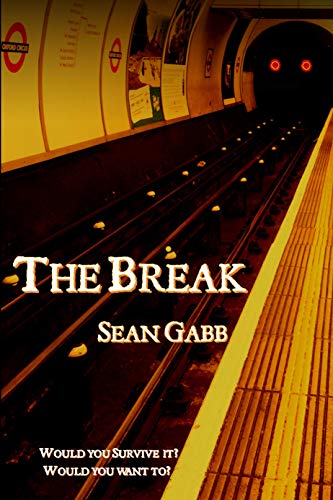

My latest recapture has been The Break. This is a dystopian satire first published in 2014 to very little effect. It got some good reviews and was nominated for the Prometheus Award, but sold only a few thousand copies. It is now available through me, and a 60 per cent royalty on another few thousand sales would be much more than the 7.5 per cent I got on first publication. It would buy me a newish car.

Unless I have pressed the wrong button, the Kindle version of the book is available for free this weekend on Amazon. If you have any trouble getting a free copy, ask me, and I will send you a free pdf. All I ask in return is a brief review on your local Amazon. Because they can be seen at the point of sale, these are far more useful advertisements than newspaper reviews.

What makes the book of potential current relevance is its backstory of disrupted supply chains and the resulting mass-starvation. The novel itself is a thriller set almost a year after the catastrophe struck England, and so the story of what happened is told in casual asides. Here are the two longest of these. They are about fifty pages apart, so don't follow each other.

1

It wasn’t even a year—but it might have been a decade, or a whole age, for all that had passed. Jennifer could remember the day, when, after endless assurances in the media that everything was under control, the shops had run out of food. Or, if there was still food, no one had been allowed the fuel to transport it. The looting of homes had begun within hours. It was now that those who’d previously broken the law, and accumulated weapons against a chance of breakdown that few really believed would come, could think themselves lucky. But they were the minority. The begging—by those who hadn’t stocked up, or had lost their stocks at gunpoint, or those who had neither contacts nor things that others wanted to buy—had been pitiable. The frantic pleas of the starving had been terrible to behold—terrible and, once the police began raiding anyone who, by giving charity, showed he had a surplus, quite unavoidable. It had toughened those who had. It had prepared those who had not, but who still managed to survive, for their place in the new order of things. And, once the gulf of The Hunger had been crossed, this new order had emerged as quickly and as logically as the movement of iron filings over a magnet.

Jennifer let her eyes rest on the Hill of the Dead. So many times she’d seen it. So many times, she’d passed it by with a shudder, or with indifference. Now, she watched as perhaps fifty labourers were allowed their time for the morning remembrance. There was Mrs Harding, the lawyer, digging tool in both hands, her lean and toughened body still wrapped in the rags that had been her business suit. There was Jennifer’s headmaster from the days when the schools were still open. His face was in shadow under his hat, and she couldn’t see the branding mark left there after he’d been denounced for cutting down a tree to keep warm. There was the little man who’d used to sell expensive chinaware from a shop in Deal. They were the lucky ones—those who had once gambled on, and appeared to do well from, a division of labour that no longer made sense, and who had survived the collapse of the old world. They stood together in memory of those they had lost, their right hands clenched into fists and beating out on their chests the now customary pattern of despair. But the ruddy man on horseback now rang his bell, and it was back to the endless work of hoeing and trenching and weeding.

Once everyone was back to work, Jennifer looked over the miles of farming land that stretched before her. There was a time when she’d have needed to wait for a gap in traffic that raced in both directions. Though she looked from habit up and down the road, all was peaceful here. The only sound was of twittering birds too small to be hunted, and of trees that sighed gently in the breeze. She turned right, and, squeezing gently on the brakes, was carried downhill again. There was a minute of pedalling as she crept uphill towards the old service station where Slovak immigrants had once earned a few pounds by washing cars. After this, it would be an easy ride back to the coast.

As she reached the edge of the built-up area, she had to give more attention again to the road. The cars themselves had long since been requisitioned for scrap. But quite a few of the owners had made sure to vandalise their property first. Even before then, cars had often been ripped open by armed men to get at the petrol. The road hereabout still had the occasional cube of glass to be avoided. Braking, she lost most of her speed, and was now coasting forward at little more than a brisk walking pace....

2

It was half a mile to the top of the next hill. Jennifer was soon used to the comparative silence. She stopped at the double junction with Lewisham Way, and rested on the edge of one of the places that must have been flattened in the Pacification. A year before, when the news reports hadn’t yet lost touch with reality, the fires in a dozen cities had flared nightly on every television screen that still worked. Safe in a house stuffed with food, and with shotgun ever loaded, Jennifer had sat with her parents and watched the beginning of the new order of things. Long before genuine footage was dropped in favour of gushing descriptions of ‘wartime spirit’ in the Cotswolds, word of mouth reporting had taken over the function of the news. Then, she’d heard of the mass shootings and the transporting of multitudes to work on the recreation of Ireland as a gigantic penal colony and food plantation.

But that was a year ago. All that marked the last stand of the hungry was the space cleared by the bombing. Even this was now being filled in by workshops to employ the poor and provide England with some of the things it had been thought the rest of the world would always send in exchange for a complex shuffling of paper. Here was a place of manufacture, not of selling, and Jennifer could now set out along a road that was mostly empty and where, from behind every bricked-up shop window, and from every old university building, came the endless hum of machinery. Twice, she passed over railway bridges and was aware of the low, continuous rumble of wagons that fed and were fed by the ceaseless whirr of steam-powered generators and machinery....

***

The Break

in paperback here

In Kindle here for free

Or e-mail me for a free pdf.

Was that worth reading?

Then why not:

![]()

|

Support this online magazine with

|

AFFILIATE/ADVERTISEMENT

This site may receive compensation if a product is purchased

through one of our partner or affiliate referral links. You

already know that, of course, but this is part of the FTC Disclosure

Policy

found here.

(Warning: this is a 2,359,896-byte 53-page PDF file!)<

L. Neil Smith‘s The Libertarian Enterprise does not collect,

use, or process any personal data. Our affiliate partners,

have their own policies which you can find out from their websites.