|

L. Neil Smith's THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 348, December 18, 2005 "I wouldn't wish that fate on my very worst enemy." A Word About Timepeeper

Attribute to The Libertarian Enterprise

Dear Readers, If you've been wondering why I haven't said anything so far about The Libertarian Enterprise completing its tenth year of publication, one reason is that there isn't very much for me to say, except "Thank You!" Thanks are due, first of all, to the individuals who have made it all possible, beginning with Yiing Boardman, our first real-live editor, to John Taylor, who stood at the wheel longer than anyone else so far, and especially to Ken "Mr. Ed" Holder, who, with his lovely and talented wife Pat, has kept TLE going through some difficult times. I wish I could thank our shortest-tenured editor, the late Dan Weiner. I also want to thank our legions of writers, far too many to list here, for their contributions over the years. Together they've helped create a unique entity on the World Wide Web, and we hope they keep it up. But most of all—and my real purpose here—I want to thank our readers for staying with us all this time, and to offer them a little something for their Xmas stockings—though I'm sure there are those (hopefully a minority) who will consider it a handful of sticks and coal. It's the only movie "treatment" I've ever written (being first, foremost, and nearly exclusively a novelist), for a feature called TimePeeper. The backstory is set in a fictional "universe" separate from the North American Confederacy or any other place I've created. In this alternate history (or the near future, if you're feeling hopeful), a Constitutional amendment passed during the first quarter of the 21st century, prohibiting enactment of any new legislation of any kind at any level of government, federal, state, or local—for one hundred years. The sole exception was bills to repeal existing laws. These are the Years of the Moratorium, divided into three periods. During the first, government didn't want to lose its power and tried everything—lying, cheating, stealing—to get around the new law. Judges, in effect, legislated from the bench, and got away with it until the moment legislators (who wanted to keep their jobs) realized that they could base a career on repealing laws, rather than passing them. I first conceived of this Moratorium idea in the early 80s, nearly twenty years before the events of September 11, 2001. I mention that because, from the initial period, I planned to write a story—more about a unique kind of genetic manipulation and government's leftover power than anything else—in which a terrorist sets off an A-bomb in Denver. During the middle period of the Moratorium, civilization begins to benefit from the steady shrinking of government. Although humanity is still subject to the usual socio-economic ups and downs, various natural disasters and so on, it's generally a happy, productive, progressive time and place, like the Confederacy, or the universe in which my novels Pallas, Ares, Ceres, and Beautiful Dreamer are set. This is the period of TimePeeper. I have no "signature story" for the third period, so far. This is a time in which the principal concern is whether the Moratorium, which healed the human race and sent them to the stars, should be made permanent. TimePeeper, as I say, was written a long time ago, and is meant as a gentle, lighthearted introduction to the libertarian concept of freedom. It never gets very serious, and in some places is downright silly. That's as it should be. Of course I retain all rights, and any copies should be credited to me. I'm looking for an agent right now with other projects (like Pallas, Ares, Ceres, and Beautiful Dreamer) in mind. But whoever ends up working for me, I'll certainly show him or her this story. Wish me luck, N. P.S. For those of you who've been wondering about Beautiful Dreamer, I'll be writing about that project, near and dear to my heart, right here, very soon.

—Film Treatment by L. Neil Smith— Against a star-filled nighttime sky, a single bright pinpoint of light looms larger ... And larger ... And larger ... At last, it occupies the entire field of vision, becoming an ominous, dull-finished, metallic spheroid—apparently the size of a small planet—its surface cluttered with minute technical detail and dominated by a broad, shallow concavity resembling a microwave receptor. It slams into an ordinary brick chimney. In fact, the object is about the size of a baseball. On a side, previously unseen, is a label: ACHRONIC SYSTEMS It bounces down the asphalt-shingled roof of a small frame garage, badly in need of paint. It free-falls twenty feet in breathless silence. Then it plops into a rusty, garbage-filled dumpster carelessly shoved up against a disintegrating board fence in a grimy, litter- strewn alley. As if from within the object, a small, tinny voice says "Shit!" In the alley, a windblown Virginia Springs Beacon bears the date May 23, 1990. ======= Suddenly it's a lovely sunlit afternoon in an entirely different place. The sky is cloudless and impossibly blue. Last winter's snow gleams high atop the peaks of some faraway mountain range. The air is clean and clear and filled with birdsong, the happy chattering of children— And an unexplained, sourceless "zinging" noise. In the background, school is letting out. The sprawling, ivy-covered building is burnished metal and tinted glass, pleasantly utilitarian and modern. Everything about the scene is colorful and glistening, as if it's just been through a cleansing rain. No pavement of any kind can be seen. Everywhere the ground is covered, either with brightly colorful carpet, or with short, thick grass. A boy and girl somewhere between 14 and 17—and looking as freshly-scrubbed as their surroundings—hurry down a ramp in front of the building toward what looks like a bicycle rack. The slots in the rack are filled with objects resembling hula hoops, but with the same dull, metallic, detail-cluttered surfaces as the ball in the opening scene. The girl is tall, shapely in a slender way, and very pretty. Her eyes are intelligent and a bit sad. Dark auburn hair brushes at her shoulders. Good-looking and cocky, the boy is an inch shorter than the girl, with medium-length brown hair and a smattering of freckles across his cheekbones. Over ordinary Levis, faded and fashionably tattered, both wear oddly-cut blousy printed shirts in hues and patterns that are not only painfully intense to look at, but which seem to shift of their own accord, changing their colors and images apparently at random. The girl even has a broad ribbon in her hair that changes to match her shirt. Both kids wear objects on their feet that look very much like running shoes, but which are more complicated in design and expensive looking. They carry no schoolbooks. They've been having a mostly-amiable argument. At the hoop rack, they're joined by another boy, very similarly dressed. "Okay, okay, I admit that you were right," the girl declares as much for the sake of their arriving friend as the boy she addresses. Something like false cheer is clearly audible in her voice and beneath it, a hint of vulnerability that she's accustomed to covering with mild sarcasm. "But we wouldn't be in this mess, Bernie Oliver, if you hadn't dragged us off on an unauthorized midnight field trip last night!" "Yeah," the newcomer agrees. He's a short, plump boy with curly orange-red hair, whose complexion consists of little besides freckles. "Friday afternoon. I still can't believe we made it through the whole damn—" The girl interrupts him: "First you talk us into stealing a timepeeper—" "Remote AnteTemporal Speculum—" Bernie corrects her. "RATS!" adds the second boy. "Like exactly how I felt when it hit that—" Despite herself, the girl grins. "That isn't what you said, Arthur." Bernie is stubborn. "Not stolen. Borrowed." The girl whirls on him. "And now irretrievably lost in the past!" She turns to Arthur for support, "Today didn't seem to last a minute longer than 10 years, did it?" To her companion: "What do we do now, genius?" "Relax, Valerie." Bernie gives her one of his irresistable grins and punches her shoulder affectionately. "We enjoyed a peek at those parts of 20th century life they don't tell us about in school, didn't we? Is it my fault that somebody stuck a chimney where I wasn't looking?" Both Arthur and Valerie roll their eyes with exasperation. "According to the readouts," Bernie ignores them, "the peeper's damaged, but isn't dead. All we have to do is get it back. I admit I haven't figured out how, but now I have a whole weekend to think about it." "Uh-oh," Arthur warns them in a lowered voice. "Look who's coming!" All three lapse into terrified silence as an enormous, heavy-set, fierce-looking man with thick white hair and a drooping handlebar moustache strides down the ramp, apparently headed straight toward them. He, too, wears faded Levis—in the form of a sharply-pressed three-piece denim suit with complex, exaggerated lapels. Only his broad necktie shifts from one garish hue to another as he passes them by without a word, intent on some private thought or errand of his own. As the tension evaporates, Bernie looks at his pale-faced friends. "See what I told you two? Old Horatius never even suspected it was missing." Releasing a ragged breath, Valerie shakes her head. "I can't take many more moments like that. Every time he walked by that cabinet, I went into cardiac arrest. A weekend to think and do something. If we don't ... " "Yeah," Arthur agrees, "If we don't ... " With a horrible sucking noise, he draws a thumb across his throat while he leers at them. Valerie and Bernie stare back at Arthur in disbelief or disgust. From their expressions, even they aren't certain which. The unexplained zinging, which they all ignore, continues. "Arthur ... " Bernie leaves the warning incomplete and turns to the still-shaken girl. For an instant she looks at him from beneath long, dark lashes, before regaining her sarcastic reserve. "Permit me to reassure you," he tells her. "Our colleague's unwarranted pessimism is without justification. Nobody is ever executed for the first offense." "Nobody's executed at all, any more," Arthur retorts. "Except at the scene and moment of the crime, at the hands of the intended victim." "He's right," Valerie almost whispers, making her eyes comically wide and fearful, "they're sent to the iridium mines on Titan, instead!" Arthur blinks. "There isn't any iridium on Titan!" "And there you have it," Bernie spreads his hands in a grand gesture, "from the Man with the Amorphous Brain, himself. So nobody has anything to worry about, right? So we'll talk about it later, okay?" He glances at his wrist where the image of an analog watch face has apparently been rubber-stamped. Nonetheless, its sweep-second hand can clearly be seen moving. The other two reflexively imitate his gesture. "My mother faxed a coupon from the 3V this morning. AcadaCom's having a trig sale and if I'm not there in 15 minutes, I'm an organ donor." Amidst appreciative grins from the other two—which in Valerie's case turns into a special smile for him—Bernie reaches for his hoop, flips it with a casual dashing gesture over his head, and, standing inside, holds it at waist level. He pauses. "Nineteen o'clock at Yoms?" They nod, reluctantly. "All right, then, let's cheat gravity!" He pushes a thumb against the inside of the hoop as Valerie and Arthur follow his example. Their hoops pulse and glow in brilliant color. Their feet lift six inches off the grass. With a whoosh—and the now-familiar zinging noise—they skim off, as dozens of other children around them are doing, into a broad, carpeted street fronting the school, teeming with other hoop-riders as well as larger, unwheeled vehicles with glowing borders around their bases. There's even a glimpse of an antique, light-encircled Volkswagen Beetle. They leave behind a low, polished granite sign, where a small utility machine (looking suspiciously like the little THX sound system robot) dabs at three rows of six-inch brass letters with a cleaning rag: ROBERT A. HEINLEIN MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOLS, INC. —QUALITY EDUCATION SINCE 2015— CAMPUS #23 VIRGINIA SPRINGS, COLORADO ======= The rusty mailbox, weed-grown and neglected since the post office went totally electronic, says ISHER in weathered letters. A picket fence sags against it. Valerie lives in the Victorian gingerbread horror behind it. The house belongs to her grandfather's unmarried sister. "Great Aunt Innelda", a charming old lady dressed for the 20th century, is clearly out of touch with the 21st. The place is strewn with photos, some more than a century old, furniture left over from a dozen conflicting periods, thousands of old-fashioned printed books, keepsakes, mementos, knick-knacks, and an indeterminate number of cats. Only Valerie's room, by contrast, is spare and tidy with its library of minidisks, data crystals, thilles, and other up-to-date electronic media, and big clock-calendar displaying the date, May 24, 2039. Whatever made Miss Isher the way she is, it wasn't the death, when Valerie was a baby, of her nephew and niece-in-law in a Lunar holiday excursion during their second honeymoon. Miss Isher speaks freely of it, scolding the long dead in absentia. Regaled by stories of the past that she's heard a thousand times before, Valerie fixes dinner for the two of them, remarkably adept with her great aunt's outdated kitchen appliances. At the table, Miss Isher gently lectures her niece for not eating enough. Valerie replies that she's going out and will eat later. Miss Isher asks if it's with that Bernard, a nice enough boy even if he seems to take Valerie a bit for granted. Valerie protests that Bernie takes everyone for granted, and anyway they're just good friends. Miss Isher smiles knowingly. She may not understand the century she lives in, but she sees that Valerie's feelings for Bernie, which have lasted since kindergarten, represent more than just an ordinary high school romance. Outside, the zinging of a hoop is heard. At the same time, a video-phone, seemingly only painted on Valerie's wrist, cheeps at her. Suddenly animated, she grabs a few things and hurries out through the leaded glass front door, slamming it behind her. Something tinkles overhead. "I always hated that chandelier," Miss Isher mumbles to herself. She watches her great niece safely down the cracked and tilting concrete walk (oneof the few left in town). The girl grabs her own hoop where it's leaning on the fence, meets Bernie, and they zoom off together. Tears glisten in the old woman's eyes as she takes a faded two dimensional photo from her mantelpiece pocket, telling the male figure within it that this is another of those one-of-a-kind relationships that sometimes happen, although, for now, Valerie would die before admitting she'll never love anyone but Bernie. They, too, she tells the person in the picture, could have been happy like that, if only he hadn't ... Too moved to finish, she puts it away and wanders out to feed her cats. The picture is of a much younger Mr. Horatius. ======= Y O M S The sign blinks, displaying the full name of the place, then the acronym by which it's best known. Yoms is a 21st century establishment perfunctorily decorated in a style three centuries old. The place is authentic 18th century in one respect: it's Bedlam, with earsplitting music, scurrying mechanical servitors, and chattering customers. Its perpetually harrassed, slovenly proprietor is stationed before a manual grill, providing an old-fashioned—if somewhat unsanitary— culinary touch in knee breeches and dirty lace cuffs. With the flat of his enormous stainless steel burger-flipper, he good-naturedly disciplines a small platoon of hovering "waitroids" wearing powdered wigs. An incongruous dusty, blue and orange banner draped across the ceiling says "Go Broncos—SUPERBOWL LXXII—Try And Win One For A Change!" On a 3V screen occupying an entire wall, a glimpse of the MTV logo, replaced by a Beatles video, demonstrates that some things do last. Valerie finds her friend Arthur in a high-backed Early American booth of artificial maple, absorbed in a plate of frenchfries and ketchup—and a tabletop screening of their final agonizing class at Heinlein Memorial High that afternoon. The table is the screen. The recording, played from a tiny box on the table under Arthur's hand and representing his notes for the day, is from his point of view at the rear of the classroom. Past seated forms of a dozen other students, the formidable Mr. Horatius is seen, lecturing on 20th century history. The irascible Horatius picks victims one by one for questioning, reducing them to utter humiliation. He mentions that he's 75 (he looks no more than fifty, due to life extension technology) and has seen a lot of history being made. Behind him, a 3V screen displays Kittyhawk, World War I, Prohibition, flappers, King Kong, World War II, Sinatra, Korea, Marilyn Monroe, the Kennedys, Vietnam, Woodstock, Apollo 11, go-go girls, urban and campus rioting, Nixon, Reagan, Ford, the forked Challenger cloud, symbols of the Soviet Union collapse, and the Waco Massacre. With what looks like Mt. St. Helens in the background, followed by Hillary Clinton, he informs them that, by the middle of the pictured century, the same people who professed concern over pollution had littered their environment with over five million federal laws which every citizen was expected to know and obey—ignorance of the law being no excuse. Corruption in high places was rampant, crime out of control. This, he says, eventually led to the Moratorium Amendment which has shaped their own century. He compels his students to recapitulate: during the "Oughts", 2000 to 2009, a Constitutional amendment squeaked by which, except for repeal of existing laws, forbade new legislation if any kind for 100 years and abolished the doctrine of sovereign immunity. The early Moratorium years, he explains, were highly tumultuous. Those in authority attempted to retain their power in devious ways. Deals among politicians prevented expected repeals. Political action shifted from the legislatures to the courts, where reinterpretation of old laws often achieved the same effect as new legislation. In the end, thanks a revival of the Common Law concept of jury nullification, genuine repeals began—gradually—eliminating "law pollution" and producing the peaceful, progressive, productive society we all enjoy today. Hands curved around an imaginary baseball-sized object, Horatius mentions a "field trip" to the 20th century slated for Monday. He paces past shelves mounted beside the screen and gestures toward a closed cabinet. On Arthur's screen, each time this happens, the boy passes a hand over his strained features, Bernie looks worried, and Valerie shuts her eyes and cringes in her seat. She does it again in the malt shop, pleading with Arthur in a small voice to "pull the chip". Suddenly, a hand other than Arthur's extracts a postage stamp sized plastic rectangle from its slot in the tiny box. The image vanishes. Valerie and Arthur turn and look upward, uncomfortably aware that someone has joined them. In fact they've been interrupted by one Moxie Morlock, one of the students visible in Arthur's recording, a school bully of the small, tough, wiry variety. As if it were any of his business, he demands to be told what their secretive huddle is all about. "Don't tell me you're rolling your hoop for Artie the Geek, now." Moxie leans in with a suggestive sneer to nuzzle Valerie's auburn hair, "And here I thought you were saving your humidity for Oily Oliver." Valerie, embarrassed into hot, blushing silence, pulls away from Moxie and keeps her eyes on the table. Arthur is about to begin an ineffectual protest, when Moxie takes the freckled boy's plate of frechfries and ketchup and rubs it all over his face. Enraged, and before he thinks it through, Arthur grabs Moxie's ever-shifting shirt. There's a breathless moment of tension. Moxie is no taller—and a good 50 pounds lighter—than than Arthur, but he's all muscle and meanness. Unnoticed by either of the boys, Valerie reaches out and picks up the fork that fell from Arthur's plate. She's about to give Moxie a surprise where it will do him the most damage, when her wrist is seized. Bernie's other hand clamps onto the lobe of Moxie's ear, his thumb pressing the dull point of a screen stylus in his fingers into the bully's flesh, threatening to pierce it, and prying him away from Arthur. Trembling with useless fury and futile resistance, Morlock pivots—against his will—until he stands nose-to-nose with his latest antagonist. Meanwhile, small robots attempt to clean up the mess centered on Arthur's face but only succeed in smearing ketchup and making things messier. Eyes locked on Moxie's, Bernie apologizes to his friends for being so long in the bathroom. He adds, just because Moxie's family ran the little mountain town for generations—before running cities fell out of fashion—that's no excuse for his barging in now, where he isn't wanted. He suggests that Moxie apologize to Valerie and Arthur for his rude, uninvited presence. Moxie begins to understand that discretion is the better part of staying alive. He obeys Bernie, is allowed to wrench free, and, amid jeers from dozens of onlookers, stalks out of Yoms. It's clear, however, that the three haven't heard the last of Moxie. Unseen in the darkness, he glares at them from outside the restaurant window, then pulls an electronic chip from his pocket and gloats. In tiny letters across its inch-square surface is Arthur's street address. ======= Some time later, Bernie, Valerie, and Arthur arrive at Achronic Systems, located on the western edge of Virginia Springs, where Arthur says his father is chief of research and development. It's the company that built the device they've lost. At the edge of audibility, there's a soft, familiar roaring in the mountain air like surf pounding on a beach. It rises and falls, unnoticed by the three. Arthur lets them in using his father's key which resembles a stiff business card. Carrying their hoops, his nervous friends want to know why he brought them here. Sorting through the contents of his pockets, he extracts another key and waves it at a pair of well-armed security robots. "These are not the humans you're looking for," Arthur tells the robots. "These are not the humans we're looking for," the low, heavy, white-enameled machines repeat the boy's words faithfully, if a bit dim-wittedly. "They can go about their business." "You can go about your business." "Move along!" he adds. "Move along! Move along!" The robots let them pass. Arthur leads his friends through the eerie, darkened plant to a hangar-like laboratory draped in black canvas where, throwing one of a pair of lever-switches to retract a set of inner curtains (he warns an experimental-minded Bernie not to throw the other; it will open outer curtains and expose them) he unveils a huge, impressive, steel- girdered ball of foot-thick glass, surrounded by complex electronic machinery. Achronic Systems is perfecting a full-sized "temporal displacer", Arthur tells them, a real time machine which, unlike the timepeeper, doesn't just show you the past, but actually takes you there. The device doesn't travel in time itself, he explains, but generates a "reality implosion", a synthetic black hole, through which objects are squeezed through the fabric of space- time from one era to another. "I have a feeling," remarks Bernie, "we're about to become cosmic zits!" Both look at him curiosly until he explaines that "zits" were a common disease that teenagers used to suffer from before the 21st century. Valerie shudders and makes a sour face. Arthur admits that the experimental device before them has never been used with living cargo. An automatic safety override, capable of snatching them back to their own century, imposes a time limit. They may become stranded in the past, however, unless, at the right time, they're in the right place: wherever the device first dropped them off. If that isn't enough, he informs his dismayed friends, there's another risk, depending on how far they are from the proper location at the appropriate moment. Too far away, he explains, and they simply remain in that primitive century—marooned for the rest of their lives. "Which might be a good thing," he offers as his friends nod in sincere agreement, "if we can't find the timepeeper and bring it back." Close enough and they may miss the machine, but still be caught within its operating field. They may reach the twenty-first century, but materialize inside something solid, generating a catclysmic explosion. With appropriate Frankensteinian ceremony, Arthur activates the machinery to transport them back to 1990 where the timepeeper has been lost. Meanwhile, Moxie has been watching from behind the black curtains. Not understanding what they're up to, he snatches up a big wrench and rushes out of hiding, meaning to do his enemies as much injury as he can. Avoiding Moxie's frantic rush, the three friends dive, hoops and all, into the displacer through a heavy-lidded port. Through a foot of glass, Arthur makes an age-old gesture. To his horror, he sees Moxie lift the wrench and smash apparatus all over the room outside the ball. Meanwhile, Bernie seizes a third remote control card from Arthur, who has somehow fumbled it out of yet another pocket. He aims it through the thick glass wall at a nearby sensor pylon, and triggers it. The giant glass ball begins to shrink and shrink, becoming smaller and smaller (which elicits hysterically frightened screams and groans from those inside and pure, gape-mouthed astonishment on Moxie's part) until it finally vanishes with a disspirited pop and a small puff of smoke. To Moxie's consternation, the displacer reappears, full-sized and empty. Frustrated, he continues smashing everything around him with the wrench, ruining the entire laboratory—including the great glass ball. As a parting gesture, he leaves the chip he stole from Arthur behind as "evidence" of who committed the vandalism, not realizing that he's done his foes worse damage, having destroyed their only way home. ======= Nighttime. Sans temporal displacer, the time travelers, microscopically small, appear a few feet in the air over a now familiar-looking alleyway dumpster, rapidly grow to normal size, and fall in with a crash. "Shit!" exclaims Arthur. In disgust, they climb out of the dumpster covered with coffee grounds and banana peels. They see at once that they're in the alley behind Miss Isher's house, but it's 1990, 50 years ago. It's also too cold for what they're wearing, and the wind is blowing. Shivering, they scrape the worst of the garbage off themselves, their hoops, and one another. For some reason, their once-colorful clothing no longer changes. "There won't be any power broadcasts for another 30 years, Valerie says to Bernie and Arthur. She comments on the filth and litter in the alley. "Of course it's dirty and neglected," Bernie replies, pointing out a nearby manhole cover embossed with the words PROPERTY OF THE CITY OF VIRGINIA SPRINGS, "it doesn't belong to anybody yet. What time is it?" "Here, you mean?" Arthur takes the remote out of Bernie's hand and consults a miniscule readout. "It's 23:23 o'clock, not that it matters much any more. It's May 23rd—yesterday, minus half a century— almost exactly five minutes after you kamikazied the timepeeper into that—." "So where is it?" Bernie chins himself on the dumpster and peeks in. "What do you care?" Valerie demands, "Don't you realize we're not going home? We just escaped with our lives! Moxie 'kamikazied' the displacer, whatever that means! And I don't think he'll stop until he's found some way to blame it on us! We're marooned in the 20th century!" "I wouldn't wish that fate," declares Bernie, "on my very worst enemy." All of them agree. Arthur says his remote should find the timepeeper by detecting its operating field if it's still working. There's no signal. At Bernie's urging, perhaps because he only intends to keep his panic-stricken girlfriend occupied, they search through the contents of the dumpster, but there's no sign of the timepeeper. "Maybe," Arthur observes, "we should have shown up half an hour early and caught the thing when it fell." "A hell of a time," Bernie is dirty and disgusted, "to think of that!" Valerie is blue with the cold. Arthur observes that it looks like snow. "In May?" she demands, her teeth chattering. "It used to all the time," he replies, "before the climate changed." Bernie refrains from hitting him. The house, Valerie observes, must still belong to her great Aunt Innelda's parents, Valerie's great grandparents. Her father, the son of Miss Isher's brother, hasn't been born yet. At least Valerie knows how they can get in out of the cold. They sneak along the garage connecting the house with the alley, through the back yard, and up toward the house, climbing a ledge to peek in the window. They don't know they're being watched by the occupant of a darkened car in the alley. To their amazement, they see not only a younger Miss Isher, but a younger Mr. Horatius. Valerie recalls his picture among her aunt's keepsakes. They grew up and went to school together when Virginia Springs was smaller, but this is something her great aunt never talks about. The couple are apparently finishing a bitter argument. Horatius slams out of the house, startling Arthur from his perch, just as a uniformed figure emerges from the alley and begins striding up the walk. Before the hurrying figure can reach them, the kids fall into the thick bushes with a lot of noise which Mr. Horatius hears. So does Miss Isher. They forget their quarrel and bring the kids inside to deal with Arthur's minor injuries. For some reason the shadowy figure hangs back, unseen by either of the adults. At the window, his nose pressed against the glass and peering in, he is a very unpleasant man in a Virginia Springs police uniform who strongly resembles Moxie Morlock. Over the next few hours, the kids get a closer look at 20oth century life than they ever expected—or wanted. At one point, they watch CNN on a flat screen: a public official expounding on the War on Drugs and the "need" to suspend the Bill of Rights. From their unique historical perspective, they know he'll be among the first convicted for violating his oath to uphold the Constitution, an opening shot in the Moratorium movement that Mr. Horatius will be teaching them about decades from now. They whisper to themselves as he watches them suspiciously. And there's plenty to be suspicious about. Responding to another news story, one of them asks, "What's the IRS?" At another point, Arthur holds a real hula hoop at waist level, turning the plastic circle around and around in his hands, looking in vain for the on-off switch. In the morning, the kids watch wheeled city traffic through the window, in particular a big municipal bus, something they knew about in theory, but which they have to see—and smell—to fully appreciate. Valerie is dismayed to notice that her combination video-phone and wristwatch, composed of a micro-thin layer of "smart" molecules, has begun to wear off and that she can't stamp it back on again because the device to do it with is on her bedroom dresser, 50 years in the future. Arthur suddenly gets an idea. If they can just find the lost timepeeper they're looking for, they can send it to their century for help. Valerie argues that whatever they do, they'll have to tell Mr. Horatius something if they're to maintain their privacy and freedom of movement—20th century children were treated as slaves or pets, she reminds them—and at the same time enlist his aid. Seeing a copy of the National Inquirer lying around, they decide to tell him they're from an advanced civilization on another world. To support the fable, Valerie explains that her parents died in an accident on the Moon. A shrewd Mr. Horatius lets them get by with the story, but doesn't buy it. They're about to tell him about the timepeeper, when the doorbell rings. It's the cop from last night—with his revolver drawn. He introduces himself as Officer Melvin Morlock. Unlike Horatius, he believes the story he just heard, eavesdropping through the window. He hasn't told anyone else about it. He wants to be the first individual to bring an alien into custody. Maybe they'll let him watch the dissections. Frightened, the kids rush out the back, led by Valerie, who knows the place very well. Morlock aims his revolver and tries to shoot at them. Screaming, Miss Isher pushes his arm up as Horatius rushes to her side. The revolver goes off, and the chandelier falls with a crash. Out in the alley where they started, the kids have their hoops revved up but don't know where to go. While they're arguing about it, Morlock's cruiser comes around the corner and enters the alley, siren blaring and lights flashing. He's calling the station, hollering that he's cornered three aliens from a flying saucer. The kids zoom toward the other end of the alley with Morlock's car plowing on behind them in a wake of impact-hurled garbage cans and bursting plastic trash bags. The kids emerge into the next street. The police car misses the turn and fetches with a crunch against several cars parked on the other side, slamming into a mailbox which leaps into the air and crashes back to the concrete in a blizzard of scattered envelopes. Tires screaming and smoking as they overcome inertia, Morlock radios for back-up, repeating hysterically that he's pursuing a trio of aliens. Bernie and his friends streak off, trying to avoid swerving vehicles and startled pedestrians. Free of such scruples, the cop careens after them, catching up. At Bernie's shout, they enter a high-walled alley cul-de-sac. It appears they're trapped. At the last instant, Bernie shouts again. They hairpin, banking like aircraft, and skim out past the battered police car along one wall. The car crashes into a two-story stack of crates and boxes which avalanche and bury it. Morlock is furious. He backs his car out from under the refuse amidst squealing brakes, honking horns, cursing drivers, and secondary collisions. His windshield shattered, he snatches the car's shotgun from its clamp on the transmission hump, thrusts it past the empty windshield frame, levels it along the hood, and roars off after the three kids like the Red Baron, driving with one hand, firing with the other. Valerie is hindmost as he gains on them, blazing away. The kids whip around a corner, double-ought buckshot whizzing past their ears. They pass a corner grocery which their pursuer drives through, emerging covered with leafy produce and panty hose, his shotgun out of ammunition. The maddened cop struggles to drive and reload at the same time. Valerie shouts and the kids circuit the block again. She grabs a potato from he grocery store, slipping back in the chase. Just as Morlock has his weapon reloaded and leveled, she jams the potato over the muzzle. It goes off, emitting sparks, flames, and a cloud of black smoke. Its barrel is split like a peeled banana. Determined to get even at any cost, Morlock hurls the shattered gun away with a curse, jerks the wheel hard, rides over the curb onto the sidewalk, and forces Valerie against blurring building fronts. She crashed through an enormous window pane, into a dry-cleaner's shop which suddenly explodes, spewing glass and shredded clothing into the street. Looking back, Valerie's friends are certain she's been killed. With a noise between an anguished scream and a bellow of rage, Bernie reverses direction, boring straight for the oncoming car. Morlock, a bully and coward, veers at the last moment, losing control. The car leaps a curb, burrowing through the wall of the police station, where, covered with fallen bricks, its radiator filling the demolished squadroom with steam, it begins falling apart door by door, fender by fender. His brother officers superiors haul the dazed man from the car, disarm him, and are cuffing his hands behind his back as he tries to explain. Meanwhile, the boys hurry back to the dry-cleaner's, Bernie's grief-swollen face streaming with tears. He utters Valerie's name over and over. The store is a disaster, little more than a debris-cluttered tunnel torn through the building. As Bernie and Arthur desperately search the wreckage for her body, Valerie appears at the opened-up back of the store, having made it into the next street just before the explosion. Bernie's immediate reaction as he seizes and kisses her is one of undisguised joy—while, quite inexplicably, the girl bursts into tears. Arthur fights for their attention: sirens are coming toward them. Being chased all over Virginia Springs by a dozen police cars now, the kids aren't any closer to escape. Suddenly, Arthur's forgotten time-field detection device squawks. They head back to the alley where the signals come from, and to the dumpster, only to be trapped by the police as the power of their hoops begins to fade. Arthur explains that it's not being replaced by broadcast power, as it would be back home. Desperate, they climb into the dumpster to escape what they're sure will be a hail of bullets. Just as dozens of black-armored, Nazi-helmeted cops with automatic weapons converge on them, there's a strange glow, and the three kids begin to shrink, disappearing with a pop. They reappear in the Achronic Systems laboratory. Astonished to be back in their own time, they accept defeat where the timepeeper is concerned, and prepare to face their punishment. When they climb out of the displacer (which they don't realize looks subtly different), they're met by Mr. Horatius, a very different appearing Miss Isher, a man who looks like Arthur, and another adult couple. Horatius holds up the timepeeper. "Never did recover this from the 20th century, did you?" The three are astounded. He tells them it was found by Miss Isher, who didn't know what it was, almost as soon as it fell. As they begin to babble questions, he holds up a hand. "I've had almost 50 years to think about this. I'm still not sure I can explain it." He holds the timepeeper in his other hand, explaining that he found it among Innelda's knick-knacks after they were married. She couldn't remember what it was or where she'd gotten it. He recognized it in later years as similar to a device newly issued for classroom instruction and eventually realized that the two machines weren't just similar, they were identical, given a certain amount of wear and tear. Since the damn thing hadn't been invented until the 21st century, how had it ended up in the 20th? Well, it was a time machine, wasn't it? But who had sent it—and then lost it? He reasoned that it might have been a prank committed by some of his own future students. The instant that the thought occurred to him, he recalled three young strangers who'd claimed they were aliens, displayed a few bits of odd, futuristic technology, turned Virginia Springs upside-down for several hours, and then vanished—back in 1990. Since then, he admits, he's expected tonight's events for years, the only question being when and which students. He knew the day had come, yesterday morning, when he discovered the timepeeper missing. Their expressions in class had told him everything else he wanted to know. "But why are ... how can we be back here now?" Valerie demands, "Moxie Morlock destroyed the displacer. We should still be stuck in 1990." "Yeah," Arthur and Bernie ask, "what happened to Moxie?" "Moxie who?" the adults ask. They have to explain to Mr. Horatius—and to Arthur's father— about the acts of vandalism that took place in the laboratory, since none of it seems to have beencarried out in this ... what ... altered version of the future? They go on to tell then everything else that happened. "Such a shame," Miss Isher comments, "I always rather liked that chandelier." "About this Moxie," Horatius confesses, "I'm not certain. Perhaps in becoming involved with you 'last night', his ancestor, Melvin, ruined not just his police career—which I gather would have been successful otherwise—but the political aspirations of his unborn descendents." "No Morlock political aspirations," Bernie replies, nodding, "no generation after generation of Morlocks dominating Virginia Springs politics." "No Morlocks dominating Virginia Springs for generations," Arthur continues, grinning, "no Moxie Morlock around to wreck the temporal displacer." "Officer Morlock, I do remember—admitted to a Pueblo mental hospital for psychiatric observation. It was rumored," Mr. Horatius strains his memory to the limit, "that he and his family moved to Fresno." "I wouldn't," says Bernie, "wish that fate on my worst enemy!" All of them shudder and agree with him. "But who are you?" Valerie asks of the couple. "Come to arrest us?" "And drag us off," Arthur adds, "to the iridium mines on Titan?" He's noticed a resemblance between the strangers and one of his friends. "This is your father and mother, Valerie," Horatius says, "I can't say where your memory of them went, maybe it'll come back, but you have some catching up to do. You see, some tragedies can be prevented. Some change caused by your presence in the past—we'll never know what it was—kept them from going to the Moon." He reaches for the control to the great canvas curtains. "Some tragedies can't be helped, however." With a great deal of mechanical noise, the great curtains open around the high-windowed circumference of the laboratory. Light pours in. "Look," he continues, "the sun's just now coming up over the mountains!" He points in the opposite direction, "What do you all say to breakfast—" They take in a sight which each and every one of them, natives of the 21st century that they are, are accustomed to: an immense expanse of water stretching from as far north as the eye can see, to as far south. Western Colorado or not, it's the Pacific Ocean. "—on the beach?"

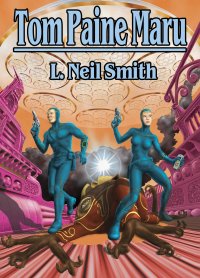

Tom Paine Maru

Help Support TLE by patronizing our advertisers and affiliates. We cheerfully accept donations!

|