|

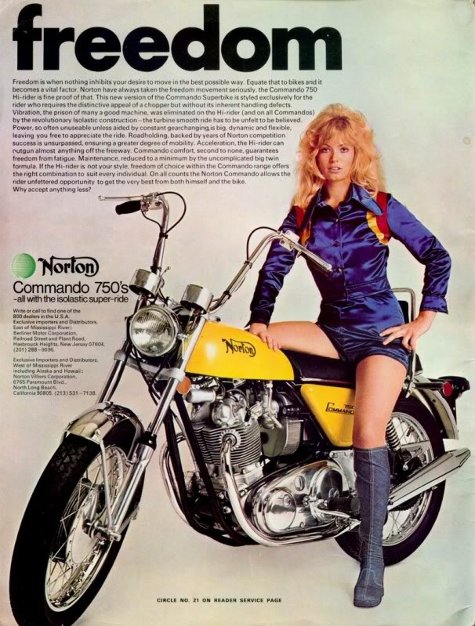

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 550, December 27, 2009 "It will not end with medicine." Attribute to The Libertarian Enterprise I have just got into re-reading Robert Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, a book I read when it first came out in 1974, a book that truly impressed me. But I have forgotten much of it, and want to see if it has aged well. First thing it did was bring back floods of memories, because this was in my heavy motorcycle period. I was in basic electronics training at MCRD San Diego, back in 1969, and decided for some reason or another to buy a motorcycle. It was a little 175cc Kawasaki with a sheet metal frame. This was before helmet laws, and I recall how thrilling it was to ride at 35mph with the wind through my hair! Well, that lasted for a couple of weeks, and then I noticed it was not much of a bike, so I decided to get something a bit more serious. I went down to a shop in National City with a bud; the shop owner's nickname was "The Guru". He had an English wife and used to take trips to England to bring back loads of old police bikes (usually Triumphs and BSA's) and a few new ones. He would chop the police bikes and sell them. He even had a couple of Ariel Square Four's tucked away in his shop. It was a place with a lot of oil on the floor, and dirty windows; one can imagine. Anyway we walked in and both of us pluncked down $1250 (paid in full!) for identical, new Norton N15's. I recall thinking the price was not bad. We could have bought an even more classic Royal Enfield Interceptor for an extra hundred bucks, or a Norton Atlas for just $950—new! Anyway, we now had about the hottest bike available in those days, with the most beautiful gas tank in motorcycledom, and a nice, grunty 750cc Norton Atlas engine shoehorned into a Matchless frame, the whole thing weighing less than 420 pounds or so. Norton marketed these bikes to desert racers, although I never got into that. Anyway we figured it would be a while before we got bored with these bikes. British bikes are crude things. They are often beautiful in the esthetic sense, until you get close to them and see the crude castings and oil drips on the floor. One gets a picture in the mind of a bunch of old farts back there in England, probably socialists, with beer guts and grease under the fingernails, sitting there putting bikes together, not having much in their tool boxes besides hammers and files. Same old design as back during the war, just tweaked a bit. Those bikes were simple, and designed to be worked on. A good thing, as they always needed attention. This was why the Japanese killed the British motorcycle industry. Japanese precision meant that you could leave the maintenance to an "expert". I'm glad I didn't start with a Japanese bike, because I would never have learned to wrench on motorcycles and cars if I had. Since the Brits assumed owner/maintainers, they also produced amazing shop manuals. Not the usual things you see these days, almost impossible to read; but real works of art, with exquisite line drawings and a fine command of the English language (it was England, after all). Made working on a bike fun. I knew another old shop owner who said that when he was young, he got hold of one of those Matchless 500cc thumpers and raced it in the '50's. Said he took it apart down to the last bolt, polished and fitted the parts properly (which those old socialists probably didn't bother doing), got it working properly, rode it all over the country. You could actually do that sort of thing with these bikes, despite how unlikely it sounds. Needless to say, you knew your bike backwards and forwards when you have done it. This gets back to a theme in the book. We are fooling ourselves if we think hiring "experts" to solve all our problems is a good way to go. It changes us from, say, engineers (essentially) and mechanics, into consumers. From independent souls into dependent waifs. In the Mountain West it seems there is only one motorcycle brand, Harley. What I have never understood is why, with a simple, antique engine technology as Harley's have, so few owners wrench their bikes. Why ride old technology if you don't take advantage of the prime reason for having it? I suppose with Harley prices so high, people are afraid to break something. Well, I later got a Norton Commando, had it for 25 years! I now have a Honda, a VFR700. Still an old bike, and cheap it was, but not so much fun to work on. Why? Because it was not designed to be worked on by owners, and because the shop manual is crap. Maybe the "good old days" of Brit bikes weren't worth a damn after all; but still, I miss them.

TLE AFFILIATE

|