|

THE LIBERTARIAN ENTERPRISE Number 610, March 13, 2011 "Much food for thought"

I Like Big Knives Part 2

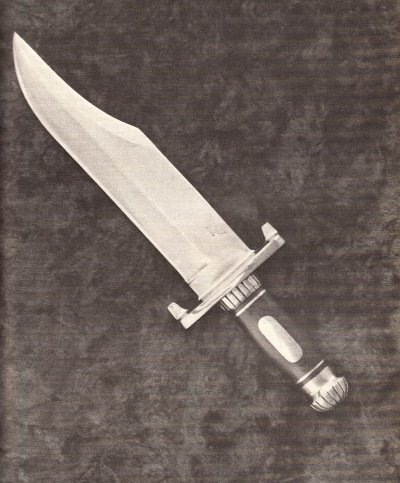

Attribute to The Libertarian Enterprise In the first item in this series, I quoted Russell T. Johnson, Arkansas culturalist and researcher, who defined a Bowie knife as being " ... long enough to use as a sword, sharp enough to use as a razor, wide enough to use as a paddle, and heavy enough to use as a hatchet." I agree with that definition, as far as it goes, and celebrate it. This is not the first time I've written about what one article proclaimed "The American Excaliber", nor will it be the last. What follows in this instance is a cultural, rather than a technical, definition of one of the two best knife designs our species has ever created. Nothing mysterious about it: the other is the Nepalese kukhri. Many knives make commercial claims to be Bowies, but a great many of them are not. This isn't a tragedy, there are a lot of good knife designs in the world. But in order to be called a Bowie knife, an artifact has to possess some or all—a preponderance—of certain elements. The first element is that it must be large. Opinions vary as to what that means. It's hard to remember that some folks—high school principals, for instance—think of a six-inches as large. William Frederick Cody—"Buffalo Bill"—famously carried a Bowie with a sixteen inch blade. The remarkable Confederate infantryman's "D-guard Bowie" blade is seventeen inches long, entering the realm of the sword. Except for theatrical eccentrics like Cody, knives began to shrink as handguns got better. The traditional length is anywhere from nine inches to fourteen, with twelve inches being a classic favorite. But like most people today, I carry a large folder clipped inside my pants pocket. Nobody knows for sure what James Bowie's original knife looked like. I read when I was a boy that the common knife of the time was a "Spanish dagger", resembling a large, inexpensive chef's knife. The Bowie brothers—there were a passle—liked to wrestle, shoot, and throw knives. Tradition is that James cut his hand as it slipped past the handle onto the blade, and brother Rezin (pronounced "reason") added a double metal crossguard to prevent such accidents in the future. That guard is the second element of a proper Bowie, meant to protect your hand from your own knife, rather than the knife of your opponent.

The next, and, in my view, only other absolutely mandatory element of a Bowie knife is called a "clip", usually resulting in a negative curve, to produce a "pointier" point, and also to drop it down onto the line of thrust. As a rough guide, line up the rivets, if any, in the handle, and the extension of that line should intersect with the point. This greatly helps minimize the risk of thrusting with a bent wrist. The real question is, how soon does the clip start, how much of the blade is involved. It's a major reason for so many variations on Bowie design. Start it too near the hilt, you end up, basically, with a double-edged dagger that's too light to fight a heavier blade. Start it too late, way up by the point, and it's virtually useless for thrusting. The great pity is that so few of them are sharpened on the back. Here is a selection of Bowie-type knives, ranked by the percentage of their blade-length taken up by a clipped point or false edge:

So: big Knife. Clipped point—if the so-called "false edge" created is fully sharpened, doubling the tactical value of the weapon, so much the better. Heavy double crossguard of brass, bronze, nickel silver, iron, or steel. Even within these strict criteria—the three necessities large size, clipped point, and double guard—there's plenty of room for variation. For example, almost all traditional and commercial knife handles are too short (although the Japanese seem to get it right, more often than not). Not only should there be enough handle and pommel to balance the blade (no more than a quarter inch ahead of the guard, for my preference) but to use as a lever to steer the big steel paddle around. Some Bowie knives feature a brass strip or rail along the back, behind the false edge. Sometimes it's a square-sectioned rod, inset in the top edge of the blade. Sometimes it's simply a section of brass channel that laps over each side. The traditional purpose of this feature is parrying, to catch and slow the other guy's blade before you turn it away. It also works against another disaster: fighting knives are big and heavy and could no doubt sheer right through the guard and the hand behind it. Brass rail is also pretty, and lends weight to the blade. I added one to my little Connecticut Valley Arms kit, and plan to add one to the big Bowie I designed as soon as I find proper channel material—it's made for edging .25 inch sliding glass doors.

I was—and remain—skeptical when the sawteeth, or whatever they were, started showing up on the backs of some "survival" knives in the 1980s, partly inspired, I suspect, by the formidable sawback of the Swiss army's "pioneer" bayonet. To a certain extent, they were intended, I'm sure, as threat-display, which I do believe is an absolutely legitimate function in knife-fighting. Less charitably, they were meant to sell big expensive slabs of steel to gullible morons. Lately, however, I've seen some sawteeth that might actually work. On a whim, I bought a $20 hollow-handled Bowie-shaped survival knife at a gun show in Laramie (well, I had to buy something) and quickly discovered that the saw's teeth were properly cut and had an actual set. I think I'm going to keep this knife in the car, get rid of the matches, needles, and fishhooks, and fill the handle with silver dimes. Another sawback that looks and sounds impressive (I confess that I have no personal experience with it so far) is that on the Spivey Sabertooth, one of which I think I have to have. (Somebody tell my wife—she has her fingers in her ears and is chanting "I'm not listening to Neil!" over and over.) The guy cuts iron water pipe with it! Knife handles offer artistic opportunities because they can be made of many things: wood, animal bone, real or fake ivory, real or fake fossil material, antler, horn, all kinds of plastic, even some other metal like aluminum or brass. Micarta is interesting—and surprisingly expensive—consisting of paper, glass fiber, canvas, linen, or other materials impregnated with a thermosetting substance called phenolic resin under high pressure. It says here it was invented by George Westinghouse in 1910, using materials created by Leo Baekeland, the Belgian chemist who invented Bakelite. Grips can be carved, engraved, or wrapped in cord, wire, or leather like a tennis racket. The best wrapping material I ever found is some silk fly-fishing line from the 1940s that I took from one of my dad's broken casting reels. Under magnification, you can see it consists of a tightly woven yellow jacket, wrapped around silk fiber. I applied what I had to a dagger-handle I made from the fork in a deer's antler, and it looks and feels great. I've tried to find more line since then, but have consistently struck out. These days, of course, it's all synthetic monomer. People get unnecessarily shirty about hand-made custom merchandise as opposed to mass-produced products, like wine or beer or chocolate snobs. Many a maker depends on it. But the fact is, it's appropriate—and uniquely so—for Americans to employ mass-produced weaponry. It was the flintlock rifle—a deliberately inexpensive design, and one of the first items ever to be mass produced—that allowed every family here to own a gun and to win and hold onto our independence. Factories in Sheffield, England, supplied half the cutlery to both sides in the War Between the States, often engraved with brave (if contradictory) mottoes like, "Death to Abolition" and "Death to Secession". But I believe the most mundane factory steel today is going to be superior to almost any steel made in the early 19th century, or, for that matter, any steel that can be concocted by hand. And I've never had a satisfactory answer to the question, doesn't the structure of Damascus-style blades (I'm not talking about Japanese folded steel, here) allow them to be penetrated easily by moisture and begin to corrode? The Bowie knife can be a useful tool—the ironic fact is, it's much better than a hatchet—but principally it's a sidearm, a "spare magazine" from an historical period when guns were still too costly, and it took a long time to reload your pistol or revolver. It's often been observed that a knife—or a sword—will never jam or run out of ammunition. But it isn't terribly useful for self-defense at twenty yards. Just remember that old line about who brings a knife to a gunfight. A dead guy. Advised by various experts, I used to tell people to keep the long edge up in a knife fight, the idea being to hack or chop at shoulders and arms with the short edge, and penetrate and disembowel with the long edge. I confess that thanks to a number of other experts, I'm no longer so sure of this upside-down tactic. The proper curve or "belly" on the Bowie's long edge gives you a weapon capable of thrusting like a sword, hacking like an axe, or making long, deep "passing" cuts, like a saber, scimitar, or katana. There is math involved in designing a Bowie's belly, but I'll leave that for another day. It's said that James Bowie beheaded a man backhandedly with the "false" edge of his knife. Author's note: manufacturers and purveyors of knives who wish to see

their products reviewed by this column are invited to write to me at

TLE AFFILIATE

|

So what we've got so far is a big knife with a crossguard.

So what we've got so far is a big knife with a crossguard.

Broad-bladed Bowie knives can be made of steel—either cut from

billets or forged together in a "Damascus" pattern (the prettiest are

fashioned from old steel cable)—stainless steel, and might even

work in bronze. Legend has it that the semi-mythical Arkansas

blacksmith James Black made a knife to order for James Bowie out of

meteoric iron, which has a high nickel content and acquires carbon in

the forging process. If this legend isn't true, it certainly ought to

be.

Broad-bladed Bowie knives can be made of steel—either cut from

billets or forged together in a "Damascus" pattern (the prettiest are

fashioned from old steel cable)—stainless steel, and might even

work in bronze. Legend has it that the semi-mythical Arkansas

blacksmith James Black made a knife to order for James Bowie out of

meteoric iron, which has a high nickel content and acquires carbon in

the forging process. If this legend isn't true, it certainly ought to

be.